Artists' Self Portraits - Part 01

- Diamond Zhou

- Aug 9, 2024

- 7 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

August 10th, 2024

Self-portrait has long been a critical medium through which artists explore and express the complexities of their identity, social standing, and inner life. This genre, where the artist becomes both subject and creator, has provided a profound platform for self-exploration and cultural commentary across different historical periods and artistic movements.

Edgar Degas, Self-Portrait, ca. 1855-56, Oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 16 x 13 1/2 in. (40.6 x 34.3 cm). Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gustave Courbet, The Desperate Man, 1844–45, Oil on canvas, 17 3/4 x 21 5/8 in. (45 x 55 cm). Private Collection, image courtesy of Conseil Investissement Art BNP Paribas.

Louis-Leopold Boilly, Grimacing Man (Self Portrait), 1822-1823, Chalk on paper.

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Self-Portrait with Two Pupils, Marie Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) and Marie Marguerite Carraux de Rosemond (1765–1788), 1785, Oil on canvas, 83 x 59 1/2 in. (210.8 x 151.1 cm). Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Las Meninas, c. 1656, oil on canvas, 125 1/4 x 108 5/8 in. (318 x 276 cm). Image courtesy of Museo Nacional Del Prado, Madrid.

Gustave Courbet, a prominent figure in the 19th century, famously declared, "I am the most arrogant man in France. I am Courbet." His self-portraits, The Desperate Man (1844-1845), exemplify his bold self-assurance and his challenge to traditional artistic norms. Courbet's intense gaze and dramatic gestures in this painting reflect his desire to position himself as a revolutionary artist, one who defies conventions and embraces the rawness of reality.

During the same period, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, a celebrated French portraitist, used self-portraiture to assert her place in the male-dominated art world. In Self-Portrait with Two Pupils (1785), Labille-Guiard not only portrays herself with confidence and poise but also includes her two female students, thereby highlighting her role as an educator and mentor. This work challenges traditional gender roles.

The Baroque era brought with it artists like Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez and Rembrandt van Rijn, who dove into the complexities of self-representation. Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), while not a traditional self-portrait, includes the artist within the composition, asserting his presence and status at the Spanish court.

Ferdinand Hodler, Night (Die Nacht), 1890, Oil on canvas, 46 x 117 3/4 in. (116.5 x 299 cm). Image courtesy of Obelisk Art History.

Night (Die Nacht) (1889-1890) by Ferdinand Hodler is a pivotal piece in Symbolist art, showcasing the artist's profound exploration of themes such as mortality, fear, and the subconscious. The expansive painting presents seven nearly nude figures, including Hodler himself, positioned in a dark, undefined space. A ghostly figure, representing death, looms menacingly above the figure that resembles Hodler, who recoils in fear. Meanwhile, the other figures remain absorbed in their sleep, embodying the universal human experience of vulnerability when faced with the unknown.

M.C. Escher, Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935, lithograph, 12 1/2 x 8 3/8 in. (31.7 x 21.3 cm). M.C. Escher works © Cordon Art-Baarn-the Netherlands.

Katsushika Hokusai, Self-Portrait as a Fisherman, 1835. Image courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago.

Henri Matisse, Self-Portrait, 1945, Black conte crayon, 16 1/2 x 12 5/8 in. (41.9 x 32 cm). © 2020 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2017.169.

Self-portrait serves as a critical medium for exploring identity, allowing artists to confront themselves while projecting personal experiences and psychological states through expressive means.

Käthe Kollwitz, a German Expressionist, used her self-portraits to express the anguish and grief she endured due to the traumas of war and personal loss. Similarly, Vincent van Gogh’s self-portraits, capture the tumultuous emotions that characterised much of his life. Pablo Picasso’s engagement with self-portrait reflects his continual reinvention of style and persona. As his works progressed, the abstracted features and intense focus on his eyes speak to Picasso’s awareness of his fear of death and his attempt to capture the essence of his being.

This delicate balance between authenticity and performance is a common thread in self-portrait, as artists navigate the tension between presenting a true reflection of themselves and constructing a particular persona.

Lucian Freud’s self-portraits, characterised by their raw realism, exemplify this tension. Freud’s intense self-scrutiny borders on brutality, challenging conventional notions of beauty and identity by focusing on the physicality of the human body with all its imperfections. Egon Schiele, another artist known for his expressive self-portraits, approached the genre with similar intensity. His works are marked by angular lines and exaggerated forms that convey psychological tension and existential angst, exploring themes of sexuality, mortality, and the fragility of the human condition.

Francis Bacon, renowned for his visceral and often disturbing imagery, used self-portrait to delve into the darker aspects of the human psyche. For Bacon, self-portrait becomes less about capturing a physical likeness and more about expressing the existential horror that pervades his work.

Käthe Kollwitz. Self-Portrait Facing Forward, 1934, Charcoal on paper, sheet:

13 7/8 × 10 1/4 in. (35.2 × 26 cm). Image courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-Portrait as a Painter, 1887-88, Oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. (65.1 x 50 cm). Image courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1628, Oil on panel, 9 x 7 1/4 in. (22.6 x 18.7 cm). Image courtesy of Ricks Museum.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait, 1659, oil on canvas, 33 1/4 x 26 in. (84.5 x 66 cm). Image courtesy of 2024 National Gallery of Art, Andrew W. Mellon Collection.

Pablo Picasso, Self Portrait with Cloak, 1901, Oil on canvas 31.9 in × 23.7 in. (81.1 × 60.2 cm). Image courtesy of Musee Picasso, Paris.

Pablo Picasso, Self-Portrait, 1971.

Lucian Freud, Reflection (Self Portrait), 1985, Oil on canvas, 32 × 23 3/4 in. (51.2 x 56.2 cm). Image courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Edvard Munch, Self Portrait with the Spanish Flu, 1919, Oil on canvas, 59 1/16 × 51 9/16 in. (150 × 131 cm). Image courtesy of Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design.

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait, 1911, Watercolour, gouache, and graphite on paper, 20 1/4 x 13 3/4 in. (51.4 x 34.9 cm). Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Self-Portrait, 1979, Oil on canvas, Each: 14 3/4 × 12 1/2 in. (37.5 × 31.8 cm). © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Gerhard Richter, Self-Portrait, 1996, Oil on canvas, 20 1/16 × 18 1/8 in. (51 × 46 cm). © Gerhard Richter 2022 (03032020). Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Marcel Duchamp, Self-Portrait in Profile, 1957, Cut and torn paper on velvet-covered board, 13 1/4 × 9 5/8 in. (33.7 × 24.4 cm). © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Josef Albers, Self-Portrait (facing right) I, 1916, Linoleum cut, 11 1/2 x 8 5/8 in. (29.2 x 22.0 cm)

Some artists use self-portrait as a powerful tool for social commentary, each drawing on their unique cultural and personal experiences to critique societal norms.

Yue Minjun's self-portraits, characterized by his trademark laughing figure, often serve as a satirical commentary on the absurdity and dehumanization inherent in contemporary society, particularly in the context of Chinese political and social realities. Cai Guo-Qiang, while known primarily for his explosive artworks, his self-portrait addresses issues of identity and cultural displacement, challenging the viewer to reconsider global narratives of power and history. Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits are deeply intertwined with her political beliefs and her experience as a woman in a patriarchal society. Her works, rich with symbolism, address issues of gender, identity, and post-colonialism, asserting her place in a world that often marginalised her.

Cai Guo Qiang, Self-Portrait: A Subjugated Soul, 1985-1989, Gunpowder and oil on canvas, 65 7/10 × 46 1/2 in. (167 × 118 cm). Image Courtesy of Cat Studio.

Yue Minjun, Dark Sky, 2003, 51 x 35 in. (130 x 89 cm). Image courtesy of the artist.

Frida Kahlo, The Wounded Deer, 1946, Oil on masonite, 8.8 in × 12 in. (22.4 cm × 30 cm). © Copyright www.FridaKahlo.org.

Louise Bourgeois, Self Portrait, 2006, Aquatint, drypoint, etching, and engraving, , plate: 10 7/8 x 13 7/8 in. (27.7 x 35.3 cm); sheet: 12 5/16 x 15 7/16 in. (31.3 x 39.2 cm). © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY.

Jim Dine, The Yellow Belt, 2005, Lithograph, woodcut, 26.5 x 20.5 in. (67.31 x 52.07 cm).

Robert Motherwell, Personage (Autoportrait), 1943, 40.87 x 25.94 in. (103.8 x. 65.9 cm.© Dedalus Foundation Inc / VAGA, New York / DACS, London

Douglas Coupland, Self Portrait: CMYK, RBG, SMPTE & Grey Scale, 2012, Powder coated aluminum, 480.1 x 40.6 x 10.2 cm, 327.7 x 22.9 cm, 327.7 x 22.9 cm, 142.2 x 40.6 x 0.2 cm. Private collection.

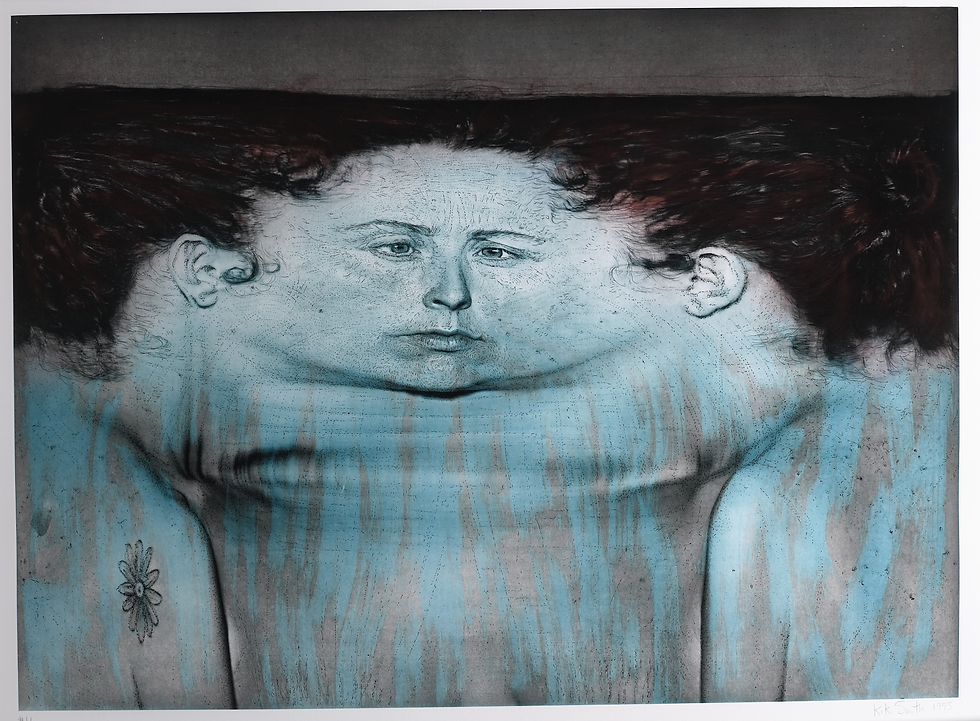

Kiki Smith, My Blue Lake, 1995, colour photogravure lithograph, 11/41, sheet: 43 1/2 x 54 3/4 in. (110.49 x 139.07 cm). Collection Buffalo AKG Art Museum.

Janine Antoni, Lick and Lather, 1993, Seven licked chocolate self-portrait busts and seven washed soap self-portrait busts on fourteen pedestals. Bust: 24 x 16 x 13 in. (60.96 x 40.64 x 33.02 cm) (each, approximately)

Pedestal: 45 7/8 x 16 in. (116.01 x 40.64 cm) (each)

In Lick and Lather, Janine Antoni created molds directly from her body, casting her likeness seven times in chocolate and seven times in soap. She then altered these casts by licking the chocolate and washing the soap, deliberately reshaping her own image. This act challenges the ancient Greek ideal of a perfectly proportioned body, traditionally believed to be seven heads high. By employing everyday materials, Antoni evokes the viewer’s memory of these fundamental rituals, fostering an empathetic connection to her process. The viewer can imagine her intimate interaction with the sculptures, mentally reconstructing the process as they engage with the work.

Marc Quinn, Self, 1991.

In Marc Quinn’s 1991 sculpture titled Self, he began to use his body as raw material for the piece. He made a cast of his own head and filled it with 10 pints of his blood immersed in frozen silicone. To keep the piece in a solid state, its temperature is maintained at -0.4°F (-18°C).

Marc Quinn’s Self adheres to this tradition, initially created during a time when the artist was struggling with alcoholism. Themes of dependency are central to both the creation and preservation of the piece. As Quinn notes, the need for the sculpture to be connected to a power source to maintain its frozen state symbolizes the concept of reliance: "Things needing to be plugged in or connected to something to survive." Without electricity, the sculpture would melt, highlights the fragility of both the artwork and the artist’s state at the time. Quinn produced a new Self sculpture every five years over the course of 20 years, marking the passage of time and his evolving relationship with these themes.