Painting is the Grandparent of All Mediums

- Diamond Zhou

- Jun 27, 2025

- 13 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

June 28th, 2025

“Don’t you know that painting is dead?”

It’s the longest-running joke among those of us who love painting—and perhaps the most enduring myth in the art world. There is something irreducibly human and something primal in the act of painting. For many, no other medium comes close to offering its intimacy, its immediacy, or its capacity for transcendence. So, is painting dead? This is modernity’s biggest challenge, if painting reigned as the paramount visual art for centuries, the 19th century brought challenges that shook its primacy. Yet no other medium has been declared “dead” so often, only to rise again, only to stubbornly persist and reinvent itself. Painting is often described as the “grandparent of all mediums”, an ancient art form from which newer visual media have sprung, and against which they continually define themselves.

The story of painting begins in prehistoric darkness. Deep in caves like Lascaux and Chauvet, early humans painted bison, horses, and mysterious symbols by firelight. These images, some dating back over 30,000 years, represent one of the very first expressions of the human impulse to create art. Remarkably, the Paleolithic painters demonstrated skills that we often think of as “advanced”, their animals show keen observation, movement, even a kind of perspective. The art critic Jonathan Jones observes that “cave artists could do it all. The faces of the animals they painted are exquisite portraits, while their bodies are rendered in perfect perspective”, challenging the traditional art-historical narrative that such techniques were later inventions. Cave painting suggests that the ability to depict and interpret the world through images is “part of the toolkit of the human mind,” not a slow accumulation of tricks over millennia.

Cave paintings mark “the moment consciousness makes an entrance”, as Jones vividly writes, a point in evolution when humans began not just to live in the world, but to reflect it back through imagery. Prehistoric paintings of handprints stencilled on cave walls poignantly announce “we were here” across tens of thousands of years. Some scholars argue that these cave images had spiritual or communal functions. Archaeologist Jean Clottes, for example, notes that chambers like Lascaux’s Hall of Bulls could accommodate groups for ceremonies, and that the painted animals might have played a role in “the celebration of rites, in the perpetuation of beliefs…and in recruiting the aid of invisible powers”. In other words, painting, at its very inception, was more than decoration. It was a means to record reality, to tell stories, to invoke the sacred, and to externalize human consciousness. Little wonder that painting would become the progenitor of so many later art forms: it tapped into something elemental in human nature. As the contemporary painter Gerhard Richter observes, “painting is one of the most basic human capacities, like dancing and singing”. It has been with us since our beginnings as a species, and its primal power still resonates.

As civilizations advanced, so too did painting. From the frescoes of Pompeii to the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, the practice flourished, adapting to the cultural shifts of each era. However, it was during the Renaissance and Baroque periods that painting fully established itself as the centrepiece of Western art. In these periods, artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo unlocked the secrets of perspective and anatomy, achieving a level of realism that had never before been seen.

Yet, even in an age of mastery, the greatest painters continuously pushed the boundaries of what painting could achieve. Caravaggio’s bold realism in the late 16th century, such as The Musicians (1597), is startling in its veracity, portraying real, everyday figures in scenes of divine importance. His use of light and shadow, chiaroscuro, imbued his works with an intensity and immediacy that was revolutionary at the time. Caravaggio’s refusal to idealize his subjects brought a raw humanity to religious narratives, a dramatic shift that would influence countless artists across Europe.

Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), meanwhile, raises profound questions about the nature of representation itself. The painting’s complex composition, which features the artist at work in the royal studio, blurs the lines between reality and illusion. By inviting the viewer into the painting’s space and implicating them in the act of creation, Velázquez achieves a level of self-awareness that defines much of the history of modern art. In this way, painting became a mode not just of depicting the world, but of reflecting on the very act of creation itself.

The 19th century brought new challenges to painting’s position at the centre of visual culture. The most immediate threat was the invention of photography. In 1839, Louis Daguerre revealed the first practical photographic process, and legend has it that upon seeing a daguerreotype, the academic painter Paul Delaroche exclaimed, “From today, painting is dead.” Delaroche’s dramatic pronouncement captured a widespread fear: that the camera, with its uncanny ability to capture reality with mechanical precision, would render painstaking realistic painting obsolete. After all, why hire a portrait painter when a camera could fix your likeness in minutes? Why commission a landscape when the new medium could document nature with all its details?

Yet, once again, painting did not die. It adapted. Rather than competing with photography’s literal representation of reality, painters began to explore the subjective, emotional, and ephemeral aspects of experience. Édouard Manet confronted the challenge head-on. His unidealized depictions of modern life, coupled with his flat, unmodulated brushwork, deliberately broke from the academic tradition of realism. Manet’s paintings were not about capturing reality, they were about confronting the viewer with the unvarnished truths of contemporary existence.

Crucially, Manet’s generation and those after him found a new raison d’être for painting in the face of photography. Painters like the Impressionists realized that a painting could capture fleeting light and subjective vision in ways a black-and-white photograph could not. Instead of competing with the camera’s literal accuracy, painting embraced its own nature: colour, texture, and the personal hand of the artist. Even as academic critics of the 19th century derided the loose brushwork of Impressionism as “unfinished” compared to a photograph’s clarity, forward-thinking writers like Charles Baudelaire sensed that painting was not dying but changing. The focus shifted to what one might call the experience of seeing, rather than mere transcription of appearances. It’s telling that by the end of the 1800s, painters had explored avenues of pure colour and emotion (in Symbolism, Impressionism, Expressionism) that had little to do with photographically accurate representation. In effect, photography’s challenge liberated painting from a burden of realism it had carried since the Renaissance. The grandparent art had more tricks up its sleeve.

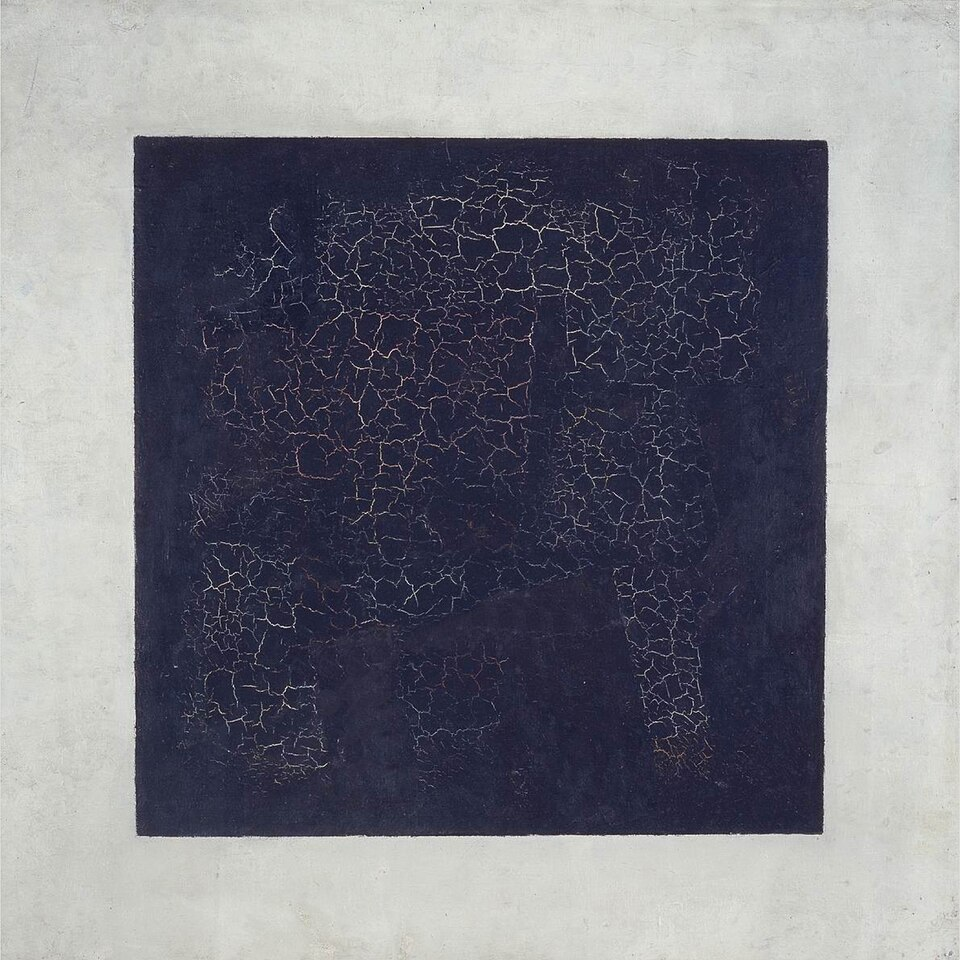

By the early 20th century, painting faced yet another wave of declarations about its demise. The rise of abstraction, collage, and conceptual art seemed to signal the end of painting as we knew it. The advent of works like Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915), with its rejection of representation in favor of pure abstraction, marked one of the most radical moments in painting’s history. Malevich’s assertion that he had reached the "zero point" of art seemed to foreshadow the ultimate death of painting. The following years saw other artists similarly push painting to the brink: the Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian reduced painting to grids of lines and primary colors, seeking a kind of pure visual harmony; the Russian Constructivist Alexander Rodchenko exhibited three monochrome canvases (red, yellow, blue) in 1921 and declared he had “reduced painting to its logical conclusion and ended it.” These acts were in part utopian, attempts to start art anew from a blank slate, but they also were interpreted as self-negations of the medium.

But again, painting did not vanish. Instead, it transformed. Abstract painters like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko pushed the boundaries of the medium in new directions. Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field painting were not merely reactions against figurative art; they were explorations of emotion, gesture, and the very nature of perception. Painting, in this new incarnation, no longer needed to represent the world, it sought to convey the artist’s inner experience of it.

Even in the face of modernism’s radical innovations, painting remained a vital force. By the 1960s, critics like Clement Greenberg argued that painting’s essence lay in its flatness and its embrace of the two-dimensional surface. For many artists and critics coming of age in the 1960s and ’70s, Greenberg’s formalist purity was stifling, and they rebelled by taking art off the canvas entirely – into performance, conceptual art, earthworks, or immersive installations. These new forms often explicitly rejected painting as antiquated or bourgeois. Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd, for one, found painting increasingly irrelevant next to three-dimensional works and novel materials. Conceptual artists of the 1970s argued that idea was more important than craft, and some, like Joseph Kosuth, flatly declared traditional painting and sculpture to be exhausted forms.

If painting is the “grandparent” of all visual media, it has shaped and influenced its progeny in profound ways. Photography, cinema, digital art, and even sculpture have drawn from the vocabulary of painting, either by mimicking it or by responding to its innovations. Early photographers looked to painting for models of composition and genre, as noted earlier. Even as photography matured, it continued a conversation with painting. In the 19th century, photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron or Oscar Rejlander staged allegorical scenes that deliberately mimicked the look of Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

Sculpture and installation art might seem more distant relatives, since they occupy space rather than flat surfaces. Yet historically, painting and sculpture were sister arts, often combined. In the modern era, some sculptors explicitly reacted against the dominance of painting, for instance, the Minimalists of the 1960s championed three-dimensional, industrial materials partly to escape the painterly “hand.”

Finally, digital art and new media might be seen as the great-grandchildren of painting. In our current era, artists use code, generative algorithms, or virtual reality to create immersive visuals. Yet tellingly, many digital artists align themselves with painting’s concerns, visuals still grapple with issues of colour, form, representation versus abstraction: all fundamental questions painting has always dealt with. One could argue that painting’s grandparental genes show up even in cutting-edge digital art.

Throughout these historical twists and turns, one might ask: what is it about painting that keeps it relevant, that newer media can’t quite replicate? What remains unique to a painted work that allows painting to survive every “death” sentence?

One frequently cited quality is physical presence and aura. A painting, traditionally, is a singular object, often with a notable material texture, and an “aura” that comes from being the unique original made by the artist’s hand. In his famous 1936 essay, Walter Benjamin argued that mechanical reproduction (like photography and film) destroys the aura of an artwork, that special feeling of authenticity and presence one gets in front of the original. Painting epitomises this aura because each brushstroke is literally a trace of the artist’s gesture frozen in pigment. The art historian James Elkins eloquently describes a painting as “a cast made of the painter's movements, a portrait of the painter's body and thoughts.” In other words, paint records the most delicate nuances of touch: whether the painter pressed hard or gently, whether a line was drawn slowly or in a sudden flourish. Elkins calls paint “a finely tuned antenna, reacting to very unnoticed movement of the painter's hand, fixing the faintest shadow of a thought in color and texture.” By contrast, a photograph, for all its realism, is made by a machine at the click of a button; it doesn’t convey the process of its making in the same tangible way a painting does. This may explain why people still report a special thrill in front of a famous painting that no digital reproduction can fully give. Let’s say standing inches away from Van Gogh’s Starry Night, one can see the ridges and swirls of paint that his brush left – literally the index of his physical presence and emotion on that June night in 1889. That embodied connection across time is something painting offers unlike any other medium.

Related to this is the time and attention painting demands, both in creation and in viewing. In our age of speed and distraction, a painting on a wall asks the viewer to slow down and engage in a sustained, often silent dialogue. Critic Dave Hickey lamented a change in viewers’ habits: “It used to be that if you stood in front of a painting you didn't understand, you'd have some obligation to guess. Now you don't.” Hickey’s wry comment suggests that contemporary audiences sometimes expect not to have to do the work – perhaps because museums and wall texts feed interpretations, or because in a media-saturated world, people are less practiced in visual patience. But painting, at its best, quietly demands that effort. It’s not that painting is wilfully obscure (well, sometimes modern art is), but that it communicates in a non-linear, all-at-once way that can’t be translated to a quick message. As Richter put it, “to talk about paintings is not only difficult but perhaps pointless… Painting has nothing to do with [what] words can communicate.” The corollary is that to experience a painting, one must engage with it on its own visual terms, an increasingly radical proposition in an era of 280-character tweets. This “difficulty” is actually a strength: it makes painting a space of refuge for complexity and ambiguity, where meanings are not reducible to slogans.

Furthermore, painting’s long history is itself an asset. Each painting carries the genes of its ancestors; it can deliberately cite or subvert past styles. This gives painting a richly layered context that newer mediums had to build from scratch. When Kerry James Marshall paints a large figurative canvas in the 1990s of Black figures at leisure in a Chicago park (Past Times, 1997), he is in conversation with Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass, with Seurat’s Sunday on La Grande Jatte, and with a whole lineage of pastoral and history painting, except now populated by Black bodies that those canonical works omitted. Marshall’s work, as The Art Story notes, “places Black figures as the protagonists of his paintings, challenging the historical absence of Black individuals from art history”. Marshall has deliberately made his figures very dark-skinned – using an ultra-rich, matte black paint – as an emphatic visual statement. He explains, “When you say Black people, Black culture, Black history, you have to show that… [Blackness] is not just darkness but a color.” In doing so, he both nods to the figurative painting tradition and boldly reshapes it. Standing before one of Marshall’s canvases, like De Style (1993) which depicts a Black barbershop in a composition winking at Dutch Old Master scenes, one experiences the resonance of centuries of painting coalescing in something urgently contemporary. Marshall himself said that when he completed his first monumental Black figure paintings, “It seemed to me to have the scale of the great history paintings, mixed with the rich surface effects you get from modernist painting. I felt it was a synthesis of everything I’d seen, everything I’d read, everything that I thought was important about the whole practice of painting.” Here is a key to painting’s resilience: it is a medium of synthesis. A single canvas can be a battleground for disparate ideas, a meeting place of past and present, high and low, personal and political, all resolved into form and colour. Other mediums can of course layer meanings too, but painting’s combination of tactile immediacy and historical density is hard to duplicate.

Finally, there is the aspect of process and discovery in painting, which artists often describe in almost mystical terms. James Elkins calls painting “alchemy”, a kind of magical interaction with substances whose outcomes aren’t fully predictable. In the studio, painters often talk about a dialog with the work: the paint “speaks” and they respond. “Painting is an unspoken and largely unrecognized dialogue, where paint speaks silently in masses and colors and the artist responds in moods,” Elkins writes. This intimate, iterative process means that paintings often carry within them the history of their own making – pentimenti (earlier marks that were painted over but faintly show through), texture that reveals layers applied and scraped. To paint is often to enter a state of concentrated flow, and viewers can sometimes sense this embedded creative energy.

To call painting the “grandparent of all mediums” is to acknowledge its seniority and wisdom, but also to imply a certain frailty or obsolescence that comes with age. The enduring philosophical and artistic significance of painting lies in its ability to adapt without losing its core identity. Painting is not “superior”, each medium has its strengths. But painting’s “grandparent” status is evident in how it underlies and informs so much of visual culture. Even the revolts against painting have been crucial in shaping painting’s subsequent directions, almost like rebellious children who, after asserting independence, later recognize what they inherited.

In the broader cultural imagination, painting still symbolizes art itself in a way few other mediums do. One speaks of “art” and the image that often leaps to mind is a person with a brush before an easel. This is not mere nostalgia; it reflects a deep-seated connection between painting and the very notion of visual creativity. Perhaps painting’s most profound offering is its reflective depth, in an age when images are abundant but often shallow, painting invites us to think and feel more deeply. It is, to borrow a phrase from philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the act of seeing from within rather than just looking from without. If we value that interior, subjective, and sustained encounter with the world, qualities that define the aesthetic experience, painting will remain relevant. The “death of painting” ultimately seems to just be a metaphor for transformation. What dies is a certain conception of painting, only for painting to be reborn in a new guise.

CURRENT EXHIBITION

TONY ROBINS: FLOWERS OF RESISTANCE

Exhibition on through August 9th, 2025.