Willem de Kooning's Woman

- Diamond Zhou

- Feb 17, 2024

- 5 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

February 17th, 2024

Willem de Kooning, Woman I, 1950-52, Oil and metallic paint on canvas, 76 x 58 in. © 2024 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Between 1950 and 1953, de Kooning made a series of works which he is best known for, the Women series. In 1953, de Kooning shocked the art world by exhibiting his "Women" paintings. These aggressively painted figural works were seen by some as a betrayal of Abstract Expressionist principles.

The Women paintings represented a commitment to the figurative tradition when artists like Pollock and Kline were moving away from representational imagery to pure abstraction. He lost the support of Greenberg, but Rosenberg continued to laud his works. MoMA purchased Woman I in 1953, a validation of de Kooning's new experiment.

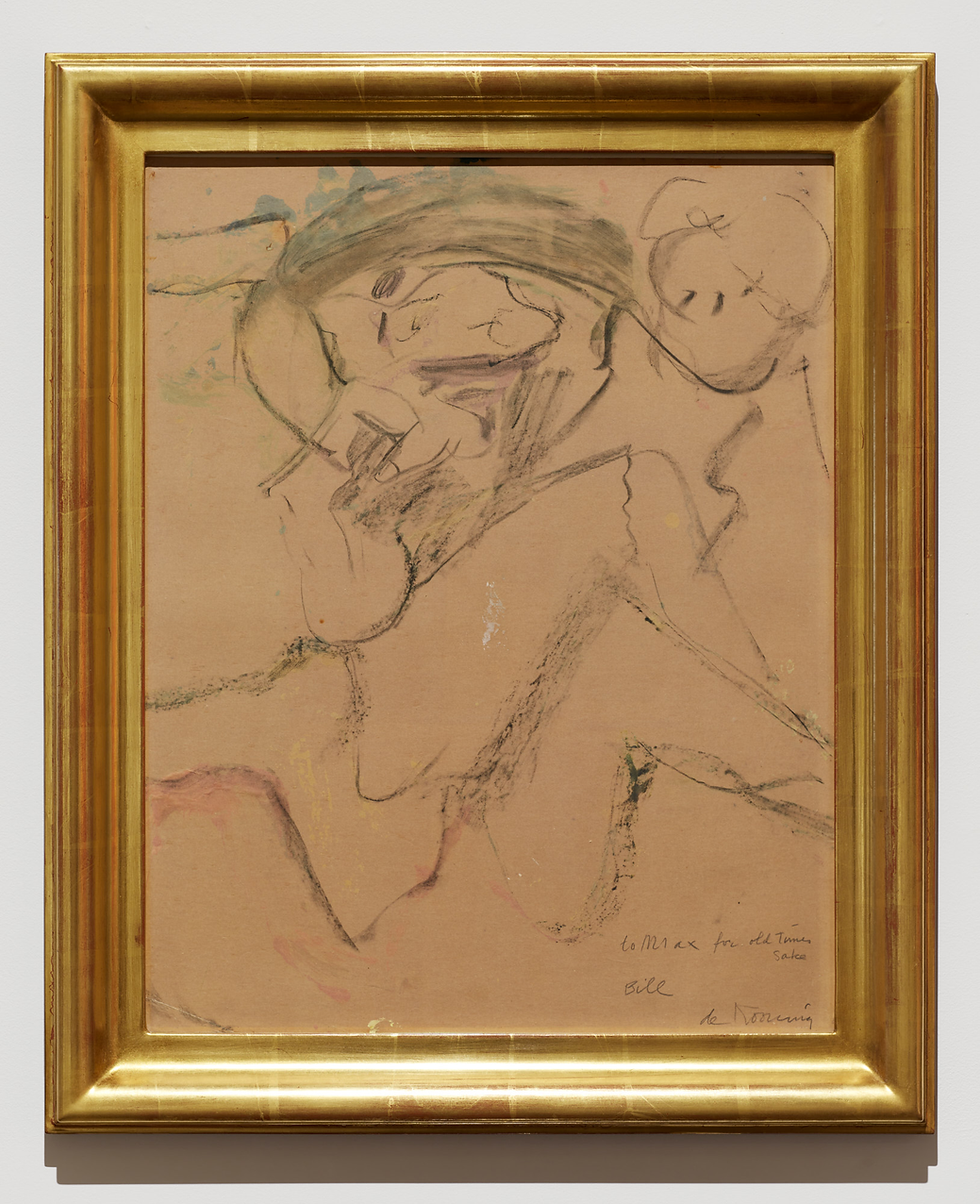

Willem de Kooning, Woman, ca. 1965, Oil, charcoal and gouache on paper laid down on canvas, 23 1/4 x 18 1/4 in.

Exhibitions: Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, March 4 - May 31, 2007; Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, "Advanced and Irascible: Abstract Expressionism from the Collection of Jeanne and Carroll Berry," Jan. 14 - Apr. 30, 2017.

Please call or message the gallery if you would like to view or acquire this work.

De Kooning was fond of working on paper, as it allowed for an immediacy that appealed to him. This small scale of this painting on paper encompasses the strength of the iconic image and the dynamic force of the lively, vigorous, and gestural brushwork. For de Kooning, art is an impulse: "Art never seems to make me peaceful or pure. I always seem to be wrapped in the melodrama of vulgarity. I do not think of inside or outside—or art in general—as a situation of comfort." Similar to his Abstract Expressionist peers, de Kooning dismisses traditional ideas of completed works or the idea of completion, each brushstroke captures speed, energy, tension, and even agitation as a form of tangible expression. This, often balanced with an equal measure of humour, results in his women figures to have a garish, grotesque, and lavish sense of expression about them.

Elaine and Willem de Kooning. Photograph by Hans Namuth, 1952.

“The Woman became compulsive in the sense of not being able to get a hold of it—it really is very funny to get stuck with a woman's knees, for instance. You say, ‘What the hell am I going to do with that now?’, it's really ridiculous. It may be that it fascinates me, that it is not supposed to be done. A lot of people paint a figure because they feel it out to be done, because since they're human beings themselves, they feel they ought to make another one, a substitute. I haven't got that interest at all. I really think it's sort of silly to do it. But the moment you take this attitude it's just as silly not to do it.”

- Willem de Kooning, Excerpt from an interview

with David Sylvester (BBC), Spring 1963

In this painting, the female figure has prominent facial features and what seems to be legs that sprawl across more than half of the painting.

“‘First of all I felt everything ought to have a mouth. Maybe it was like a pun, maybe it's even sexual … it helped me immensely to have this real thing. I don't know why I did it with the mouth. Maybe the grin—it's rather like the Mesopotamian idols.’ The reference is to two Sumerian statues that were on view at the Metropolitan Museum in the 1940s and '50s. De Kooning was a regular visitor to the Museum, drawing inspiration at various points in his career from diverse sources in art history, from the Roman paintings of Boscoreale to portraits by Ingres and the Le Nain brothers.”

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

Above photos:

Willem de Kooning in front of a portrait of his friend Max Margulis, photographed by Max Margulis.

The Blue Note founders and the Pete Johnston Blues Trio (left to right): Max Margulis, Pete Johnson, Abe Bolar, Alfred Lion, Ulysses Livingston. Photo by Francis Wolff, 1939. Courtesy of the family of Max Margulis.

In the upper right corner of the painting there is a small owl-like figure, de Kooning inscribed the lower right of the painting: “To Max for Old Times Sake. Bill de Kooning”. Max refers to Max Margulis, Margulis was known affectionately as “Max the Owl” for his horn-rimmed glasses.

“Another circle of friends in Chelsea, drawn together by a serious love for music, met once a week or so in the apartment of a musician named Max Margulis, who lived at 300 West Twenty-third Street. A violinist and singing teacher, Margulis (known affectionately as ‘Max the owl’ because of his thick glasses) was a man of diverse gifts. He was a boxer; he helped produce the fabled Blue Note jazz series; he was also, later on, an experimental photographer…Margulis owned all the newest records. ‘In those times there were not many records,’ he said. ‘A couple of Mozarts, a couple of Schuberts.’ The repertory at Max's was mostly classical, but, as Margulis noted, de Kooning also loved jazz: ‘He went to hear Louis Armstrong and all of those guys.’”

- Mary Stevens and Annalyn Swan, "de Kooning - An American Master,"

(New York, New York: Knopf, 2006), p. 145.

Willem de Kooning in front of an early state of Excavation, photograph by Max Margulis

Willem de Kooning, a Dutch-American artist who played a pivotal role in the New York City art scene and was a major figure in American Modernism and Abstract Expressionism. After arriving in the United States from the Netherlands, de Kooning worked in various manual jobs before fully committing to his art career.

He became closely associated with influential artists like Arshile Gorky and was involved in significant projects, such as a mural for the WPA with Fernand Leger. By the late 1930s and early 1940s, de Kooning, along with Gorky, emerged as an underground leader in the New York art world. His first solo show was in 1948, and by 1950, he had gained critical acclaim, notably for his work "Excavation."

Despite controversy over his "Women" series in the 1950s, which diverged from the abstract trends of the time, de Kooning continued to receive support and recognition, evidenced by MoMA purchasing "Woman I."

After the 1950s, Willem de Kooning continued to evolve and experiment with his art, solidifying his status as a leading figure in Abstract Expressionism.

Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, de Kooning explored new themes and techniques, including a series of paintings focusing on landscapes and what he termed "pastoral" or "parkway" landscapes, inspired by his surroundings in East Hampton, New York, where he moved in 1963.

In the 1970s, de Kooning's work became more fluid and abstract, with a renewed emphasis on colour and form.

This period is marked by a series of highly abstracted, lyrical paintings that further demonstrate his mastery of the medium and his ability toconvey emotion through color and gesture.

The 1980s were a challenging time for de Kooning as he began to suffer from Alzheimer's disease,which eventually led to a decline in his ability to work.

Despite his health challenges, de Kooning was honoured with numerous awards and retrospectives during this time, including a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1983, which then traveled internationally.

Willem de Kooning passed away in 1997. His legacy is that of a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism and one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. His work continuesto be celebrated and studied for its contribution to modern art, with his works held in major collections worldwide. De Kooning's influence extends beyond his paintings, impacting generations of artists and the broader trajectory of contemporary art.