Emma Lake Workshop - Part I

- Diamond Zhou

- Aug 15, 2025

- 12 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

August 16th, 2025

Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops began as a remote summer workshop and became a national engine for modern art. We are splitting this very three-dimensional and impactful topic into two parts, Part I presents an overview and follows the workshop from its beginnings through the 1960s. Part II will return to the artists in detail and trace the program’s expansion, influence, and legacy from the 1970s to the 2010s.

Hidden away in the northern Saskatchewan wilderness, the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops became one of the most influential incubators of modern art in Canada. Established in the mid-20th century as a response to the isolation of prairie artists, these summer workshops brought together local talent and leading figures of contemporary art in an immersive, retreat-like setting. Over the decades, what began as a modest regional experiment evolved into a program of national significance.

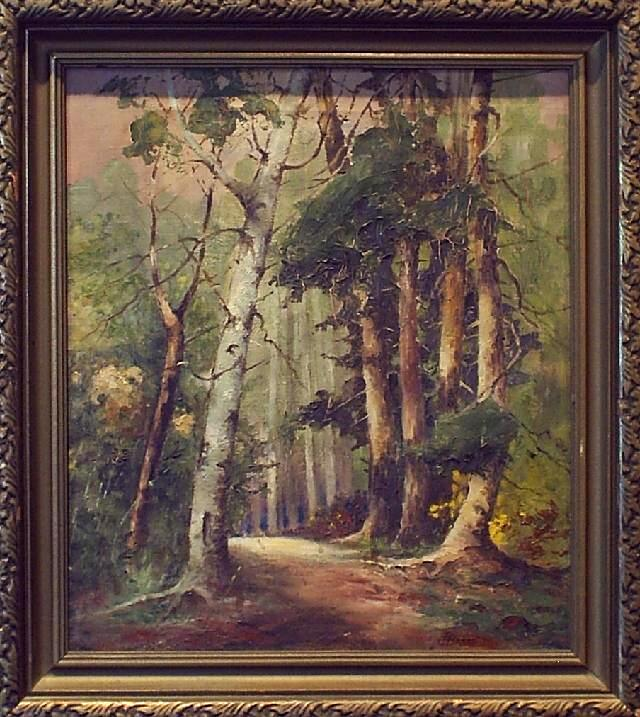

The story of Emma Lake as an art hub predates the famous workshops. In 1935, despite drought and the Depression and with the university running a deficit, President Walter Murray agreed to establish a summer art school at Emma Lake at the urging of art professor Augustus “Gus” Kenderdine. Kenderdine had trained at the Académie Julian in Paris in 1890 and brought a European landscape tradition to Saskatchewan. In 1936 the University of Saskatchewan formally incorporated the Murray Point Art School as a for-credit summer program, widely recognized as the first university credit art school in Canada, and it soon became a model for later artists’ workshops. The site would be officially renamed the Emma Lake Kenderdine Campus in 1989 in honour of its founding figure.

The school’s creation also drew on a local network of advocates. Journalist J. S. Base of the Prince Albert Daily Herald championed the idea in the early 1930s while spending summers sketching at the lake, and wrote to Murray in support of a practical art school for northern communities. Artist Ernest Lindner, an Austrian immigrant who settled in Saskatoon in 1926, helped introduce Kenderdine to Emma Lake and built a cabin on nearby Fairy Island, which later became a provincial heritage site. As the program grew, students could study art history with Gordon Snelgrove alongside Kenderdine’s outdoor classes, and the credit program functioned as a northern extension of the university’s outreach, an early form of distance and extension studies in the province.

The choice of Emma Lake, a remote, forested region north of Saskatoon, was intentional because it provided an escape into nature and a break from city life, fostering creativity in a peaceful setting. For nearly two decades, Kenderdine’s camp introduced students to landscape painting and plein-air practice in the northern wilderness, laying a foundation for Emma Lake’s artistic community.

However, by the early 1950 a new generation of prairie artists craved for more than just a nice place to work and summer classes. The art scene in Saskatchewan was relatively isolated, it is far from the hub which was Toronto, Montreal, or New York, and with few opportunities to see cutting-edge work in person. Two art professors from Regina, Kenneth Lochhead and Arthur McKay, committed modern painters themselves, and their peers craved what they referred to as outside contact from the greater ‘art world. They dreamt of a forum where serious painters and sculptors of the Prairies could learn from contemporary art movements and exchange ideas with prominent artists beyond their region.

In the winter of 1954–55, Lochhead (then director of the School of Art at Regina College) and McKay came up with a plan to organize a professional artists’ workshop at Emma Lake. With support from the University of Saskatchewan and a modest grant of $450 from the Saskatchewan Arts Board, they launched the first Emma Lake Artists’ Workshop in the summer of 1955. The timing was auspicious: 1955 was the province’s Jubilee (50th anniversary) year, and there was an appetite and a push for cultural initiatives. That August, a group of artists gathered at Emma Lake for a two-week intensive workshop unlike anything previously seen in Canada.

The Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops broke the mould of traditional art education. Rather than a having teacher-student classroom structure, these workshops were set up as creative residencies or retreats. A guest artist-leader, typically an established painter or critic invited from outside Saskatchewan would join local artists for two weeks of dedicated studio work and dialogue. Importantly, the guest was not there to give formal lessons or lectures; as Kenneth Lochhead stated, “the purpose of the program is to provide an opportunity for painters and sculptors to work and exchange ideas… under the leadership of an artist of contemporary reputation”. In practice, the visiting artist worked on their own art alongside participants, engaging in discussions and critiques, but everyone was essentially a peer. This created a collaborative atmosphere where influence flowed freely without the hierarchies of a classroom.

For that inaugural 1955 session, Lochhead and McKay invited Jack Shadbolt, prominent modern painter from Vancouver, as the first workshop leader. Shadbolt prepared a program of practical demonstrations and talks about forces shaping contemporary art. The results were electrifying. The prairie artists, many of whom had never before interacted so intimately with an outside modernist painter, found the experience transformative. Veteran Saskatoon artist Ernest Lindner declaring afterward, “I know that I can never be the same again.” The introduction of fresh ideas, from abstract painting techniques to new ways of thinking about art, had profoundly expanded the creative horizons of local artists.

Word of the workshop’s success spread quickly in Canadian art circles. Here was this remote lakeside camp in Saskatchewan producing serious contemporary art and discourse, at a time when much of Canadian art was still dominated by conservative or regional styles. The Saskatchewan Arts Board continued its support, and the University of Saskatchewan embraced the workshops as an extension of its summer program. Annual workshops at Emma Lake became a fixture each August (with occasional pauses in some years). Attendance grew as artists from across Canada applied to participate in this lively summertime studio in the woods.

By 1957, just a couple of years in, the impact of Emma Lake was already evident. A number of painters associated with the workshops began to develop reputations for bold, modern abstract art. Ron Bloore, Ted Godwin, Kenneth Lochhead, Arthur McKay, and Douglas Morton would soon be dubbed the “Regina Five.” All five either taught at Regina College or were closely connected to the Emma Lake scene, and their work was galvanised by ideas exchanged at the workshops. In 1961 the National Gallery of Canada mounted Five Painters from Regina, a high-profile exhibition featuring these artists, signalling that Saskatchewan had suddenly become an unexpected hotbed of avant-garde painting. The Emma Lake Workshops are widely credited with aiding the formation of the Regina Five group, by giving them a forum to experiment and gain confidence in their modernist vision.

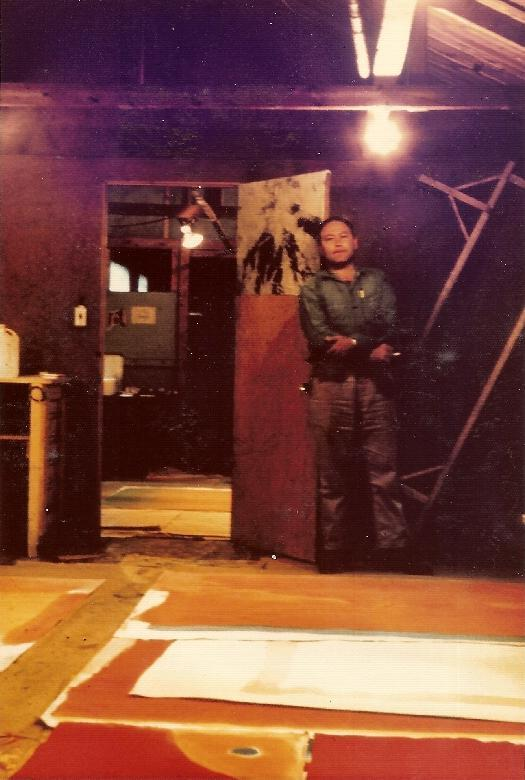

Beyond the Regina Five, many other painters benefited from the Emma Lake experience in the 1950s. For example, Marion Nicoll of Calgary attended in 1957 when New York abstract painter Will Barnet was the guest. Nicoll was already inclined towards abstraction, but her encounter with Barnet’s ideas inspired her to make a dramatic change in her art, leading to a new hard-edged style in her paintings. Similarly, young Saskatchewan-born artist Roy Kiyooka participated in several workshops around this time. Kiyooka later recalled those summers fondly, saying that he and his friends at Emma Lake “were all birthing our own painterly visions”. The late 1950s saw Emma Lake blossoming into a dynamic crossroads where local and national art trends met, and where participants felt liberated to reinvent their approach to art.

If the first few workshops ignited Saskatchewan’s modern art movement, the next decade fanned those sparks into a flame. During the 1960s, Emma Lake hosted a remarkable roster of internationally renowned artists and critics as workshop leaders, figures so significant that their presence in rural Saskatchewan almost defied belief. Under Lochhead’s continued coordination, the workshop organizers showed bold ambition in whom they invited. Major names in the New York and London art scenes made the trek to Emma Lake, attracted by its growing reputation as an artistic retreat and laboratory.

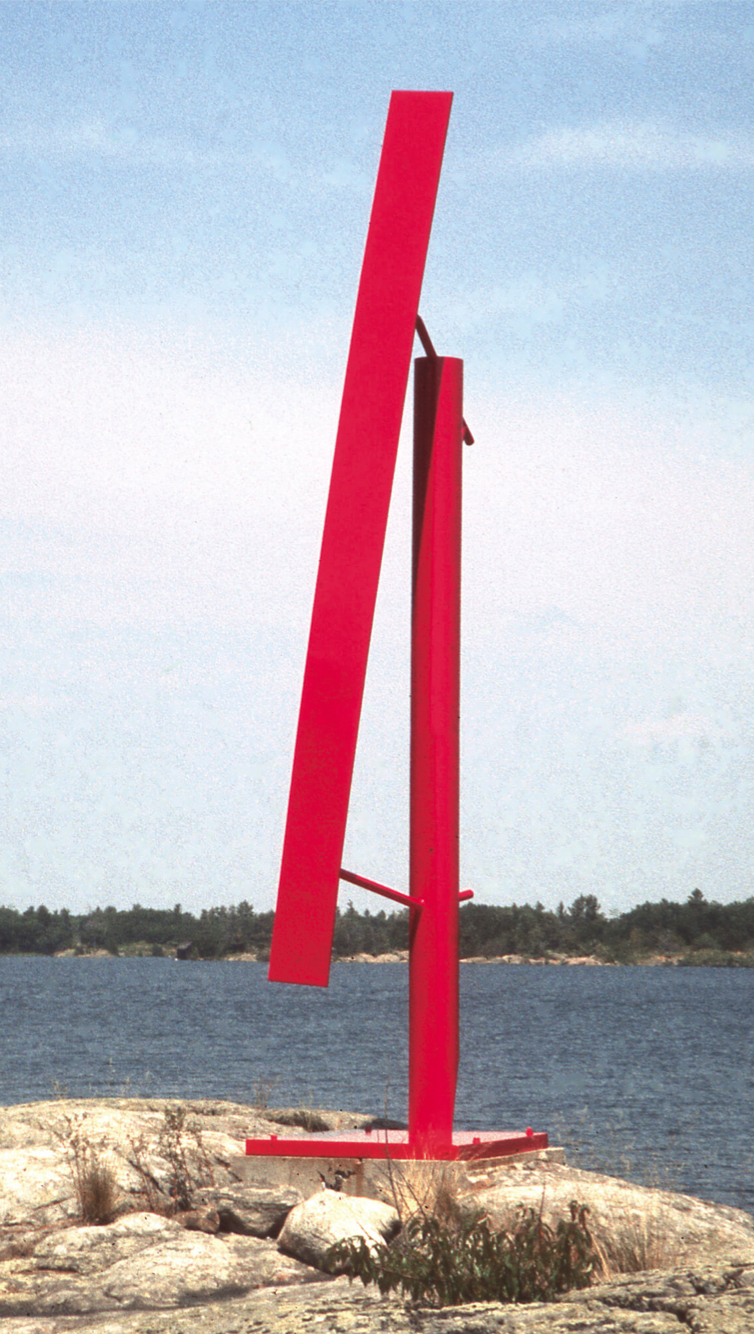

A landmark moment came in 1959, when Barnett Newman agreed to be the guest artist. Newman was a towering figure of Abstract Expressionism in New York, famous for his large fields of colour and “zip” paintings. He was initially sceptical about coming to a remote Canadian lake, upon receiving the invitation, Newman quipped, “Where the hell is Saskatchewan, and who is Emma Lake?”. When he did come, he embraced the workshop with enthusiasm. Newman spent his time at Emma Lake vigorously engaging with the Canadian painters, and did not hold back on critiques. One example, after looking at one of Arthur McKay’s pieces, Newman challenged him: “You have a really good painting here… is that all you want to do?” This pointed question, essentially daring McKay to push his art further had a profound effect. McKay later credited Newman with spurring a radical shift in his approach where he began experimenting with new techniques to give his paintings more “distinctive surface patterns,” moving beyond what he had thought possible. The same could be said of Robert Murray, whose critique with Barnet Newman paved way for his becoming a sculptor rather than a painter. Encounters like this became Emma Lake legend, the idea that a New York art icon could directly spur an artist to new heights in a collegial wilderness setting.

If Barnett Newman’s visit was legendary, 1962 managed to top it in terms of influence and controversy. That summer the invited leader was not a painter but the era’s most influential (and blunt) art critic, Clement Greenberg. Greenberg’s presence at Emma Lake in 1962 is often cited as a turning point. By then, Greenberg was famously known for championing abstract art (particularly the Post-Painterly Abstraction movement) and for his forceful opinions on quality in art. At Emma Lake, he served as a roving critic-in-residence, looking at everyone’s work and offering copious advice. Many artists found his guidance invaluable: he introduced the painters to the latest developments in American art and urged them to strive for “formal excellence” in their work. Indeed, Greenberg introduced the work of second-generation American abstract painters to the group, broadening their perspectives. He was impressed with what he saw, so much so that he later wrote in a letter, “You have no idea how much I’m betting on Saskatchewan as N.Y.’s only competitor.” Greenberg saw in Saskatchewan a fertile ground for modern art that could rival New York’s scene, precisely because of its distance and originality. His high praise gave the Emma Lake artists a huge morale boost.

However, Greenberg’s forceful personality also made 1962 the most controversial workshop in Emma Lake’s history. Ever the blunt critic, he did not shy from telling participants to abandon what he viewed as inferior techniques or subjects. It was later alleged that Greenberg pushed some artists to give up their personal style in favour of his preferred abstraction. While many heeded his advice, a few resented what felt like heavy-handed influence. This became particularly significant and polarizing. Some older regional artists bristled at Greenberg’s dismissal of their more traditional work. Yet younger painters like Kenneth Lochhead and others of the Regina Five largely embraced Greenberg’s formalist approach, seeing it as validation of their direction. Greenberg’s involvement was short-lived and contentious, the legacy of modernist abstraction in the Canadian Prairies is undeniable. In fact, Greenberg became a kind of mentor to Lochhead and other Regina painters. Under Greenberg’s encouragement, Dorothy Knowles, one of the few women artists in the group chose to pursue her strength in landscape painting at a time when abstraction dominated. Greenberg recognized her talent and advised her to trust her own vision of the prairie landscape. Knowles later attributed a significant “boost in her career” to Greenberg’s supportive critique, recalling that his voice gave her confidence to assert her artistic identity.

Throughout the 1960s, the Emma Lake Workshops thrived as a hotbed of artistic exchange. Each year brought a new notable guest and new ideas. Abstract painters Kenneth Noland (1963) and Jules Olitski (1964) both came from the U.S. Color Field movement, literally showing Saskatchewan artists how to pour and stain canvases in luminous colours. Composer John Cage (1965) exposed participants to avant-garde concepts of chance and multimedia art, a radical departure from painting, expanding creative thinking. In 1967, rising American minimalist Frank Stella arrived, followed in 1968 by the cerebral sculptor Donald Judd, each bringing the latest directly from New York to the boreal forest of Emma Lake.

It is hard to overstate how extraordinary this was: at a time when communication was limited and travel to art centres was expensive, Canadian artists were coming to Saskatchewan, dining, painting, and debating for days on end with some of the world’s leading art figures. “Artists in New York would never have a chance to have breakfast, lunch, and supper with Clement Greenberg for two weeks running in the woods,” Kenneth Lochhead later remarked. “In New York, you’re lucky if you see these people for an hour…. This way, they’re completely captive to that environment.” This golden era of Emma Lake coincided with, and indeed catalysed, a golden era for Western Canadian art. By the late ’60s, Saskatchewan’s once-isolated artists were at the forefront of major national developments.

UPCOMING EXHIBITION

GROUP EXHIBITION

Opens Wednesday, August 20th, 6:30-9:30PM

Look forward to our invitation for the opening reception

This exhibition gathers artists whose practices transform material and perception into experiences that linger, works that shift the way we see light, inhabit space, and feel the weight and presence of form. United by a balance of beauty and thought, these pieces invite us to step into moments where looking becomes a deeper act of seeing.

We are pleased to welcome Marion Landry, whose geometric abstract paintings, grounded in a deep engagement with light, perception, and phenomenology, offer meditative glimpses into atmosphere and stillness; James W. Chiang, a BC artist whose paintings merge chromatic purity and precision with an intense dialogue between passion and perception, creating what he describes as a “kinetic exchange” in which beauty and existence are unbounded by thought or time; Jan Hoy, whose elegant abstract sculptures in bronze and steel explore balance and spatial clarity; Ronald T. Crawford, a Salt Spring Island painter and sculptor whose practice unites contemporary painting with the physical poetics of stone, and whose influence reaches beyond his studio through the founding of the Salt Spring National Art Prize; and lastly, Edward Burtynsky, one of Canada’s most celebrated contemporary artists, whose monumental photographs confront the scale and complexity of our industrialised world, rendering beauty and devastation with equal and uncompromising clarity.

The exhibition also features new works by our beloved artists Michael Bjornson, Deirdre Hofer, Robert Kelly, David Spriggs, Charlotte Wall, and many more, whose evolving practices continue the gallery’s conversation with space, materiality, and form. A selection of newly acquired works will also be unveiled over the course of the exhibition, inviting visitors to return and experience how the dialogue develops.