Our Trip in Toronto

- Diamond Zhou

- Jul 25, 2025

- 8 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

July 26th, 2025

We spent a significant week in Toronto with some of the dearest people we know. Our days were filled with studio, gallery, and museum visits that opened windows into the inner workings of artists’ practices, their methods, experiments, and aspirations. Each encounter left us inspired and full of admiration, a reminder of the extraordinary courage it takes to create something truly new and visionary.

We were fortunate enough to be in the company of the celebrated Canadian art historian and curator Roald Nasgaard and his wife Lori Walters, an eminent medieval scholar. To share time with two people so brilliant and finely attuned to the life and art of past and present was such a privilege. They accompanied us to the Art Gallery of Ontario, the University Club of Toronto, and finally the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, each stop offering its own kind of revelation. These encounters, whether with monumental works or with intimate gestures of sketches, remind us why we do what we do. We pursue art not simply to catalogue its history or admire its surfaces, but to step into those rare spaces where human imagination meets the ineffable. Art allows us to trace the line between who we are and who we might become; it shapes culture, yes, but it also stirs something higher within us: an awareness, a quickening, a sense that life itself can be seen anew.

It was a week dense with beauty, thought, and gratitude, a week that will echo for a long time to come.

Our first visit together was David Spriggs’ monumental installation Aeon, housed in the atrium of Simcoe Place at 200 Front Street West. The work, concentric layers of anodized aluminium forming a concave, almost cosmic void, seemed to breathe with the shifting light of the space. As we moved around it, the sculpture unfolded as both an object and an experience: a meditation on time, vision, and the invisible structures that hold the world together.

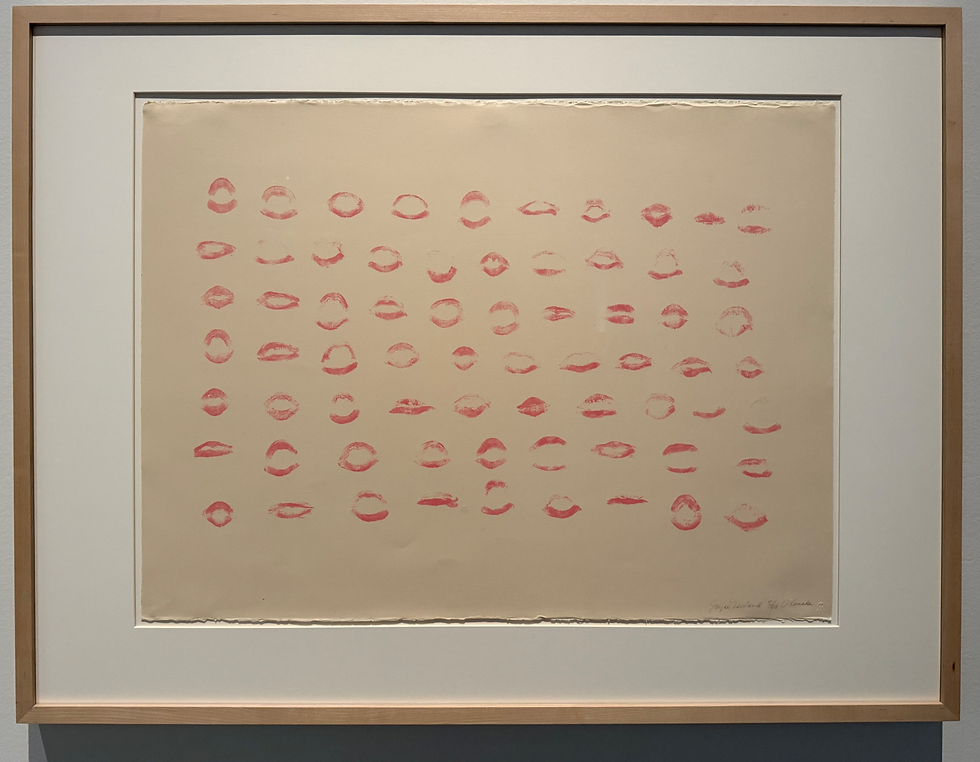

Our visit to the Art Gallery of Ontario opened with the sweeping retrospective Joyce Wieland: Heart On, co‑organized with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. This is the first comprehensive survey of Wieland’s work since 1987, spanning five decades and presented across seven gallery spaces. It includes a large body of works in media ranging from film and painting to textiles, collage, print, and embroidery—many of which have been painstakingly restored for public viewing. Wieland’s incisive inquiries into feminism, ecology, Canadian identity, and northern landscapes feel particularly urgent today.

We then immersed ourselves in Moments in Modernism, a survey of the AGO’s Canadian modernist legacy, a collection in many respects built under the tenure of our guide, Roald Nasgaard. Having him walk us through works he helped acquire as Chief Curator lent legendary resonance to each piece and renewed our appreciation not just of the artwork but of the institution itself.

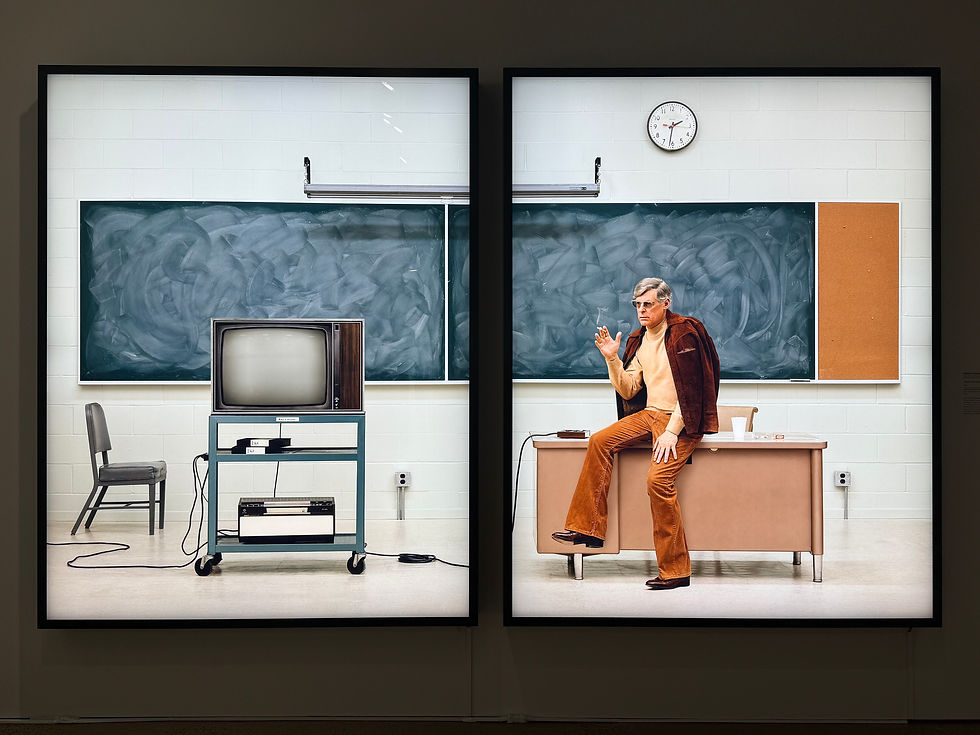

Lastly, we encountered Light Years: The Phil Lind Gift, unveiling forty‑odd works gifted in late 2024 by the estate of Philip B. Lind. This outstanding acquisition includes thirty‑seven works by Vancouver‑school luminaries like Stan Douglas, Rodney Graham, Jeff Wall, and Ron Terada, alongside major international figures. Ron Terada’s sculpture City of Vancouver, inscribed with the welcome “Entering the City of Vancouver”, anchors the installation.

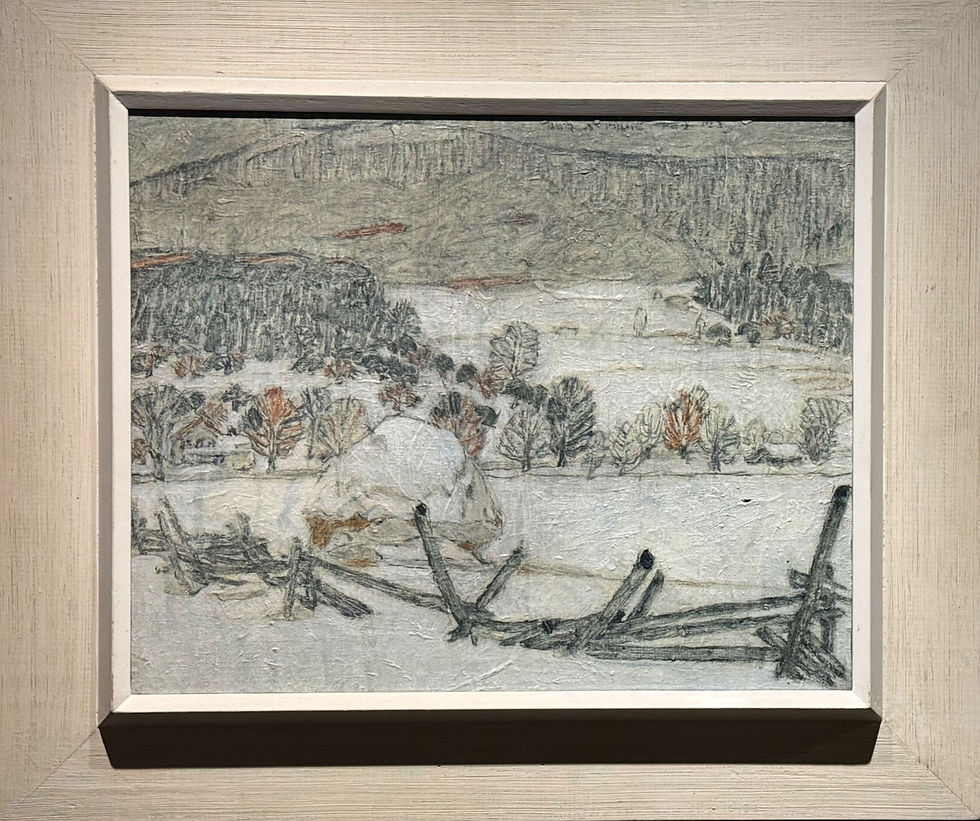

The following afternoon brought us to the University Club of Toronto, an institution where art and architecture breathe together. Founded in 1906 and housed since 1929 in its stately neo-classical building on University Avenue, the Club is steeped in history yet alive with a remarkable art collection. Over decades, it has cultivated one of the finest private assemblies of Canadian modernism, with an emphasis on works by the Group of Seven, the Canadian Group of Painters, and their contemporaries. Early stewardship by Lawren Harris, himself a member, ensured that paintings of the northern landscape and its spiritual resonance would become central to the Club’s visual identity.

Guided by Kaitlin Rogers, whose insight and enthusiasm illuminated every room, we experienced the collection as something more than a series of works on walls, it felt lived in, conversational, and quietly profound. Paintings hung in richly paneled rooms, each work holding its place in a dialogue that bridged decades of Canadian art. Kaitlin’s depth of knowledge, paired with her warm storytelling, brought to life the provenance and meaning behind the works. Leaving the Club, we were struck not only by the art itself but by how seamlessly it integrates into the building’s atmosphere, reflecting an ethos where art is not distant, but an active presence, seamlessly integrated into the daily lives of those who inhabit and care for it.

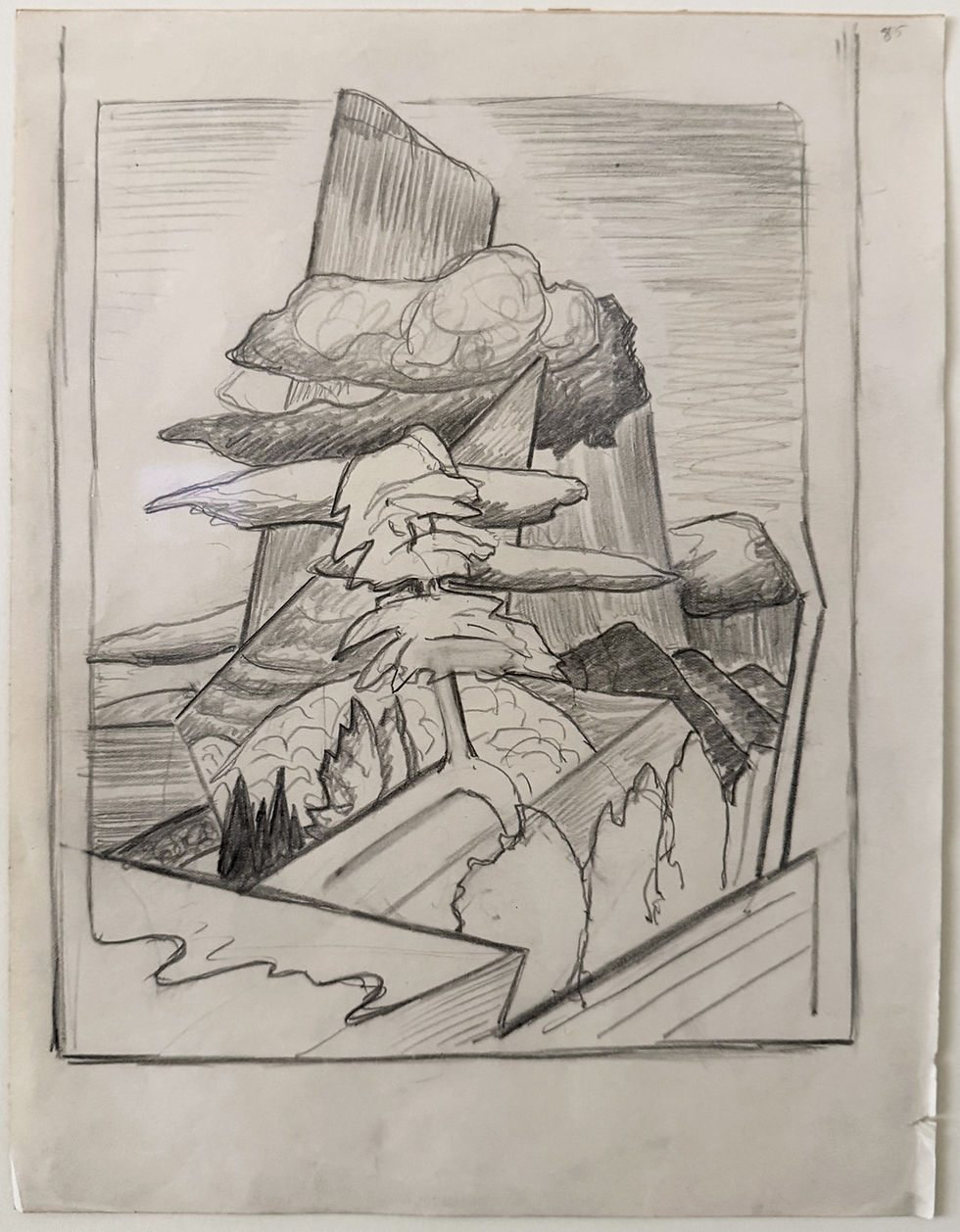

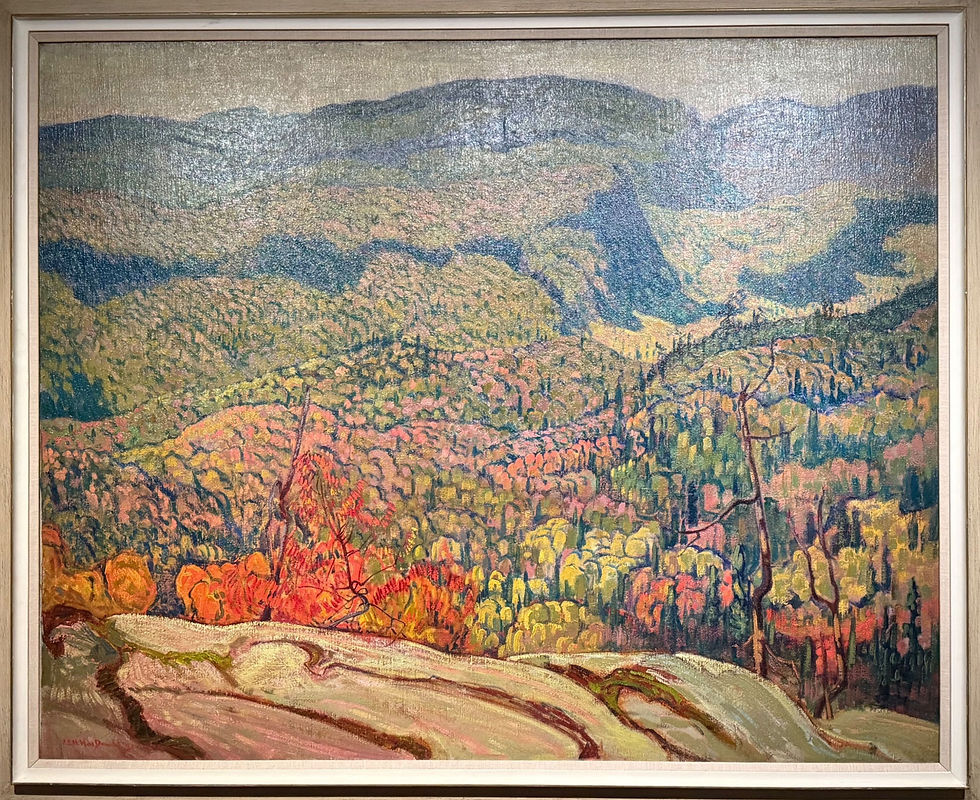

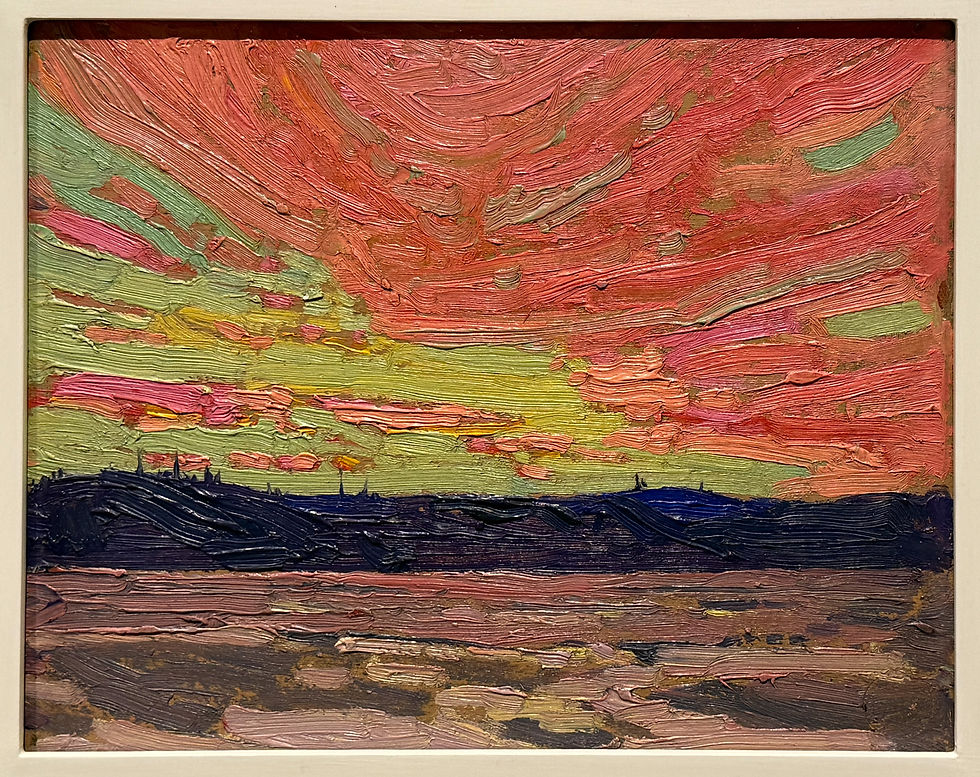

At the McMichael, our day soared under the animated guidance of Associate Curator John Geoghegan-witty, smart, richly anecdotal, and deeply versed in Canadian art. He brought the skies of Tom Thomson, the strokes of the Group of Seven, and the subtleties of Inuit and Indigenous works vividly to life. His tales transformed each gallery into a living narrative. The McMichael began when Robert and Signe McMichael purchased ten acres in Kleinburg in 1952 and started collecting the Group of Seven from 1955 onward. They formally donated the collection and site to the Government of Ontario in 1965; the public museum opened in 1966 and was incorporated in 1972. While originally dedicated to landscape art, its mandate expanded in 2011 to include contemporary Canadian and Indigenous art. Despite these changes, the museum still feels deeply connected to its original ethos—a sanctuary for Canadian art in dialogue with its own institutional roots.

A highlight was Morrice in Venice, on view May 31 to September 21, 2025. Curated in dialogue with Sandra Paikowsky’s landmark scholarship, the exhibition reveals James Wilson Morrice’s poetic, colour-drenched interpretations of Venice, his small-scale pochades and canvases capturing canals, piazzas, bridges, and skies in fleeting brushstrokes that pulse with memory and atmosphere. Walking through galleries suffused with Venice light was to feel transported, every painting a hushed epiphany, every hue a whisper of place.

Thursday night, in the company of Roald and Lori, we experienced a performance that left us both deeply moved and contemplative. MISSING, the chamber opera created by Métis playwright Marie Clements and JUNO Award-winning composer Brian Current, is not merely an opera—it is an urgent voice for those silenced. The work confronts one of Canada’s most pressing human rights crises: the tragedy of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Over its intense 80 minutes, the opera follows the intertwined stories of an Indigenous woman, known only as “Native Girl,” who disappears, and Ava, a non-Indigenous lawyer whose life is irrevocably altered by their tragic connection. Set against the stark realities of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and the haunting expanse of the Highway of Tears, the performance blends Western operatic traditions with Indigenous language and storytelling—sung in both English and Gitxsan.

The evening was as visually arresting as it was musically profound. Andy Moro’s projections wrapped the stage in shifting landscapes and emotional textures, amplifying the raw depth of the singers and ensemble. The result was not only a performance but an act of remembrance, resistance, and reconciliation.

It is rare to encounter a work of art that feels both devastating and healing at once. MISSING is one of those rare creations—one that stays with you long after the final note.

What lingers most from this journey is not merely the memory of places visited or works admired, but the way the week quietly reshaped our sense of being. There were moments standing before a painting, hearing a story unfold, sharing a glance of understanding, that felt as though the world briefly revealed itself in sharper focus, stripped of all that is inessential. Art has this rare power: it bypasses reason, reaching directly into that quiet interior where meaning takes root. It asks us to be present, to feel deeply, and to recognize beauty not as decoration, but as something transformative. To share these encounters with people we hold in the highest regard only heightened that sense of grace. What we bring with us on the next leg of our journey is not only admiration for the works themselves, but a renewed awareness of how art calls us to live, to live with attentiveness, openness, and a measure of wonder.

CURRENT EXHIBITION

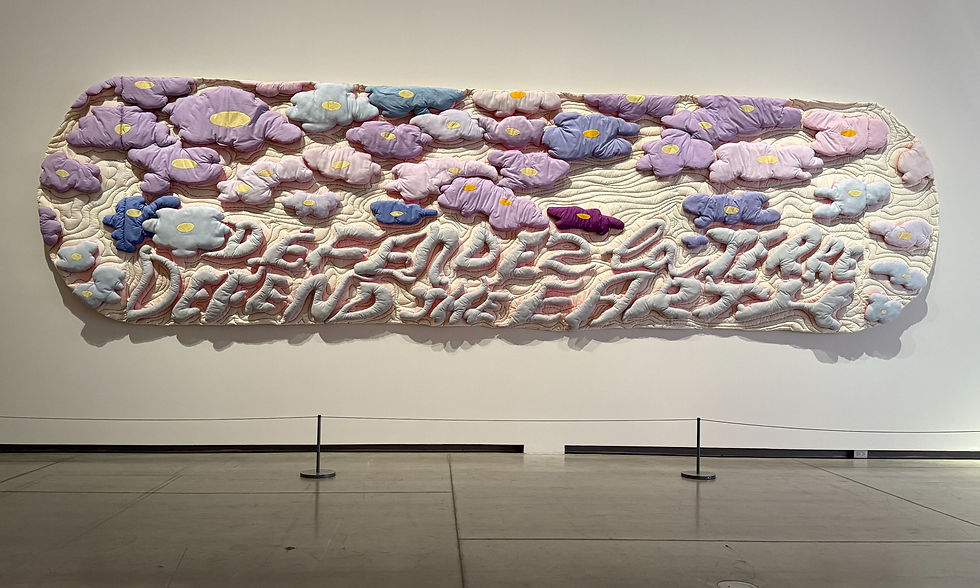

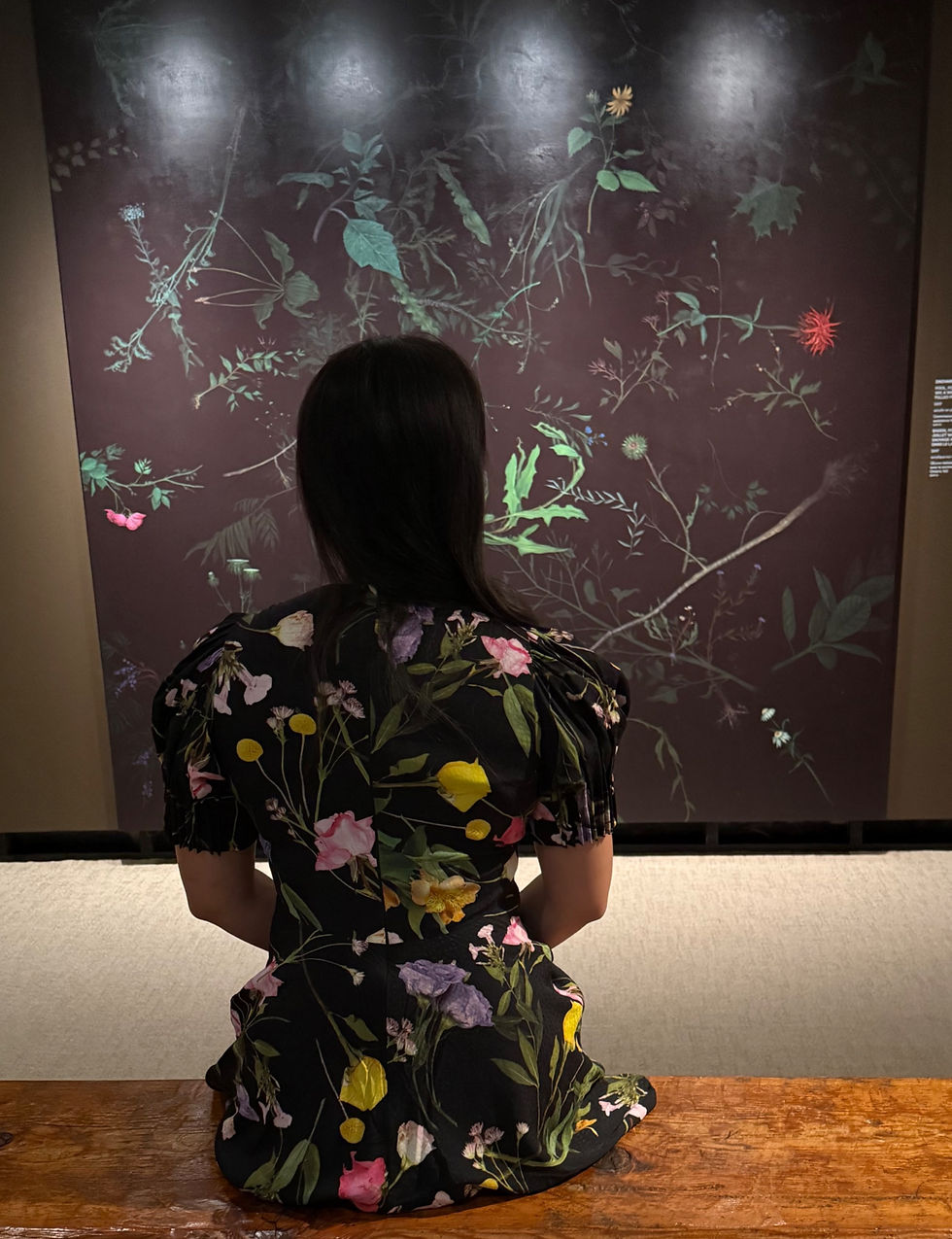

TONY ROBINS: FLOWERS OF RESISTANCE

Exhibition on through August 9th, 2025.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT

Watch TONY ROBINS’ artist talk on his solo exhibition, FLOWERS OF RESISTANCE: