Emma Lake Workshop Part II

- Diamond Zhou

- Aug 29, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Oct 28, 2025

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

August 30th, 2025

As the 1960s closed at Emma Lake, the debates that had defined the early period continued to shape the work. The program evolved, some seasons paused, others returned with new formats, and the range of participants diversified, so did problems artists brought with them. What stayed constant was the working premise, artists spent time together, spoke candidly, and let the place change the pace and focus of their practice.

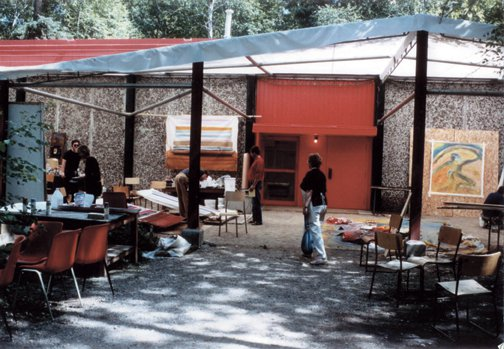

Daily routines mattered. Studios opened early, meals structured the day, and work resumed after each break. Many participants say those routines shifted their attention in ways that lasted. Artist Lorenzo Dupuis describes stepping from the car into the smell of pine and feeling city distractions fall away. In his first year he left a noisy shared cabin, moved into an older, isolated one deeper in the trees, and stayed there for years. The space became a studio and then a reliable way to work. Participants recall a large shared painting studio that could hold thirty or forty people, a separate sculpture space down a short slope in the forest with a roof but open air, a circular lakeside kitchen with windows on all sides, and a single long dining table where newcomers and veterans sat together. Slide lectures ran at night. On clear evenings there were northern lights. The walk back along the beach was often an extension of the day’s studio critiques. Facilities shaped outcomes. Two weeks could be enough to change a career. Evenings were not a pause. They were part of the method: meals as seminars, arguments as tools, the generosity of watching someone else try to solve your problem in a different medium.

What visitors remember most is not a single critique or a famous name but the density of ordinary hours. Breakfast was cafeteria style. A guest or peer would offer one practical sentence that clarified a problem. By late afternoon the studios smelled of turpentine and pine, and new work was pinned to temporary walls. Many would say the place worked on the senses before it worked on the intellect: the smell of the forest served as a reset that moved artists out of city time and into studio time.

Studio tone emphasized seriousness rather than ceremony. Robert Christie still talks about how the presence of senior artists changed what ambition felt like, how a guest wandering through and asking one pointed question could push you past whatever you thought you were doing. That authority was earned at eye level. Guests offered opinions. Participants argued back. The status of the visitor mattered, Christie admits, but it mattered most because it made people listen hard and then test ideas on the wall the same day.

Artists who grew up around the program emphasize continuity. Rebecca Perehudoff recalls moving through the connected lakes by canoe and entering studios where the light seemed designed for painting, a domestic summer that became an education. Her sister, Catherine Perehudoff Fowler, describes the workshops as a professional community that extended beyond Saskatchewan and continued to matter decades later. The idea that art is made alone might only show one facet of reality, but Emma Lake taught a different truth. Proximity sharpens the work. Community gives it lift.

Looking back in the earlier days of Emma Lake, a turning point often cited dates to August 1959. Robert Murray, then still primarily a painter, met Barnett and Annalee Newman at the lake. The discussion moved from studio to mealtime and became an ongoing exchange. Barnett Newman encouraged Murray to pursue sculpture and supported his move to New York the next year with a formal letter. Murray did not arrive as a visitor. He worked at Modern Art Foundry alongside Newman when the bronze for Here I (To Marcia) was cast, then assisted on projects in which collaboration and friendship were closely linked. Murray’s language in steel developed across the 1960s and 1970s. A work titled Tundra (for Barnett Newman) makes the connection explicit, joining the northern landscape that first framed the conversation to the discipline of a New York fabrication context.

The program’s geography was more flexible than its title implies. In 1968, when Donald Judd led the session, the workshop operated at Rapid River Lodge on Lac La Ronge. That year demonstrates that Emma Lake functioned as a portable method that could be relocated to match a leader’s needs and the logistics of a given season. Scale is also worth noting. From 1955 to 1970, 166 people attended the professional workshop. The number is modest and helps explain the intensity of the setting: a small, renewable cohort returned to the same rooms, and the conversation deepened.

Visiting leaders gave the program its external horizon. In 1977 Anthony Caro adjusted his process to the site. The site offered workable materials and space rather than heavy infrastructure. Without plate and cranes, he worked with tubing, rod, and plywood and treated steel as drawn line in space. The Emma series that followed includes 22 sculptures constructed during that workshop, a concrete output that links a legendary fortnight to documented production. Participants recall being drawn into his process and being asked for direct feedback in real time. The episode confirmed that the format could generate new work quickly and that the program could teach across media. When Caro and Robert Loder founded the Triangle Artists’ Workshop in 1982 in New York State, the structure echoed what the lake had already proven viable. Invite a focused cohort, give them time and space, let proximity and straight talk do the teaching. Emma Lake had imported the art world in the 1960s. By the 1980s it had exported a method that would travel through a network of Triangle sessions around the world. Emma Lake functioned not only as a location but as a working model.

Painting remained central through the 1970s and 1980s, but the language diversified. The early impetus from Barnett Newman’s challenges and Clement Greenberg’s critiques did not harden into a single school, instead, it opened parallel routes that artists pursued with different technical commitments.

Dorothy Knowles is the clearest example of a route anchored in direct observation. In 1962 Greenberg urged her to stay with the landscape as a serious subject, not as a fallback. Knowles took that advice and refined an approach in which sky, treeline, and water act as structural intervals, light organizes the image more decisively than drawn contour, and prairie motifs function as working material rather than emblem. Contemporary and later commentary repeatedly links that inflection point to the 1962 workshop. In 1963 Kenneth Noland arrived with procedures: stain, edge, and scale were demonstrated at full size, turning what many had only seen in reproduction into concrete options. Several accounts of Knowles’s development note the move, after these sessions, from heavier impasto toward thinned oil applications with watercolour-like transparency, a shift consistent with what Noland made available in the studio. Knowles’s own summary of the decade names the sequence of leaders: Clement Greenberg (1962), Kenneth Noland (1963), Jules Olitski (1964), and others, as pivotal exposures that consolidated a practice of working from nature with a more fluid touch.

William Perehudoff took a second route through the same encounters. After working closely with Noland in 1963 and then with Olitski in 1964, he refined a distinctive colour grammar: translucent fields and glazes set against opaque, clearly bounded forms, a bright, non-descriptive palette and a consistent attention to the interval between shapes as a carrier of rhythm. Authoritative overviews frame his mature language as a Saskatchewan inflection of Colour Field, learned in part through Emma Lake and metabolized into a local light and scale.

The Olitski session matters to both streams. He often did demonstrations and worked through staining and transitions of colours with participants watching closely. That visual, procedural access made a difference: it grounded later experiments by landscape painters seeking luminosity without illustrative detail and by abstractionists testing how thin films of colour could still carry structure.

Embedding practice at the site reinforced these directions. In 1969 Knowles and Perehudoff purchased a cottage at Emma Lake and built studios, turning the workshop into an annual laboratory and a domestic base. That continuity, arriving early, working in the specific light, returning to the same views across seasons, helps explain the durable clarity in Knowles’s later landscapes and the calibrated restraint in Perehudoff’s colour compositions.

Noland’s role is worth a brief return in this context. In 1963 he brought methods, not mystique. Participants recall that his demonstrations stripped away the aura around “stain” and “edge,” leaving transportable tools. When Noland returned as a leader in 1991, those procedures had already entered Saskatchewan’s working vocabulary. Painters were not copying Washington Colour techniques; they were adapting them to prairie light, local formats, and their own studio problems. Independent lists of workshop leaders for 1991, which include Noland alongside Nancy Tousley and others, corroborate the program’s long arc of revisiting and updating those technical conversations.

Taken together, these developments produced two stable paths that carried forward through the 1970s and 1980s. On one side, a rigorous landscape practice that treats observation as a structure problem, with light doing the organizing. On the other, a post-painterly abstraction that uses stain, edge, and calibrated opacity to make colour carry form without description. Both were taught, tested, and normalized at Emma Lake in the 1960s, then sustained into the 1970s and 1980s through repetition on site, peer critique, and the continued circulation of leaders and peers who insisted on clarity over mannerism. That is why, by the time new cohorts arrive in the late 1980s and early 1990s, stain and edge are not styles in Saskatchewan, they are just part of the toolbox.

Leadership evolved as well. Early visiting leaders were predominantly men. That balance shifted steadily. In 1977 Wynona Mulcaster, a central figure since the 1930s and a teacher who carried the program’s habits into classrooms across the province, returned as a leader. That year also listed Mina Forsyth, Edna Andrade, and Carol Sutton alongside Caro in sculpture, indicating a porous relationship between roles. In 1990 Dorothy Knowles led a session, a clear acknowledgment that the program should hear directly from artists it had helped to shape. Through the 1990s and 2000s, painters such as Mali Morris and Janet Fish kept colour, structure, and facture in active discussion. Critic curators Karen Wilkin, Sandra Paikowsky, and Nancy Tousley treated looking and conversation as work, making the workshop a thinking space as much as a making space. Landon Mackenzie co led in 1995 and has often described the intensive, no nonsense teaching culture she carried forward. In 2007 Monica Tap led with a painter’s understanding of photography and time, connecting newer image construction to long running landscape questions. In 2012 Elizabeth McIntosh led what became the final workshop before the campus went quiet, and her contemporary abstraction underscored that, to the end, the program operated as a live studio rather than a memorial to the 1960s.

Public framing followed these practices. In 1989 the Mendel Art Gallery organized The Flat Side of the Landscape: The Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops, curated and edited by John O’Brian, and issued a 150-page catalogue with essays by O’Brian, Ann K. Morrison, David Howard, Matthew Teitelbaum, and Terry Atkinson. The show then toured nationally, which is essential to its impact beyond Saskatchewan. The itinerary ran from 5 Oct–19 Nov 1989 at the Mendel (Saskatoon) to 28 Apr–10 Jun 1990 at the Art Gallery of Windsor, 22 Sept–28 Oct 1990 at the Edmonton Art Gallery, 19 Dec 1990–11 Feb 1991 at the Vancouver Art Gallery, and 1 Mar–21 Apr 1991 at the MacKenzie Art Gallery (Regina). That route placed Emma Lake squarely inside major Canadian institutions and audiences, not merely as regional lore but as a national argument about modernism, region, and method.

The program continued into the 2000s with smaller cohorts and new coordinators but with the same structure. Participants committed to the full session, ate together, accepted critique from peers and visitors, and returned to work more than once a day. People rarely describe classroom style instruction. They describe time and focus. They describe walking the room at day’s end to see risks taken by others and to test those moves against their own problems. They even note the informal social spaces nearby, including a pub many walked to through the woods, which served as another venue for exchange.

Closure came for practical reasons. The campus required significant health and safety upgrades with multimillion dollar estimates. Budgets tightened and priorities shifted. In November 2012 the University of Saskatchewan suspended activity at the Kenderdine Campus while it reconsidered the site. The response was immediate and global. Nearly fifteen hundred people signed an online petition within days, with supporters from Japan, South Africa, Belgium, and Norway, a small indicator of international reach. Alumni organized and wrote in support. In the following years, still without a reopened program, the university donated and relocated a group of cabins to address urgent housing needs in the north during the pandemic. That decision had clear public value and also made a near term return to summers at Murray Point less likely. The pattern is familiar in the arts: strong programs built on modest operating budgets can be vulnerable when maintenance and institutional restructuring coincide.

To call Emma Lake a school is accurate but incomplete. It functioned most effectively as a working environment that disciplined time and attention. The site itself mattered. The long horizon and the particular light demanded clarity and scale decisions that fed both abstraction and landscape, and that shaped approaches to drawing in steel as well as on canvas. The essential conditions remain clear: two weeks of focused work, shared meals, a culture of direct critique, and the expectation that conversation leads back to the studio. Those conditions continue to produce results, which is the most persuasive measure of the program’s legacy.

CURRENT

GROUP EXHIBITION

This exhibition gathers artists whose practices transform material and perception into experiences that linger, works that shift the way we see light, inhabit space, and feel the weight and presence of form. United by a balance of beauty and thought, these pieces invite us to step into moments where looking becomes a deeper act of seeing. Exhibition features works by Michael Bjornson, Edward Burtynsky, James W. Chiang, Ronald T. Crawford, Deirdre Hofer, Jan Hoy, Robert Kelly, Marion Landry, James O’Mara, David Spriggs, Charlotte Wall, and many more of our artists and works from our collection.