Lines of Expression

- Diamond Zhou

- Apr 5, 2024

- 6 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

April 6th, 2024

The line, in its myriad forms, serves as the foundation of visual art, embodying both the simplest and most profound expressions of artistic vision. The line requires thorough investigation, exploration, and discussion. This brief discussion barely scratches the surface of the vast array of insights and perspectives that lines contribute to artistic dialogue.

18th century English artist William Hogarth theorises the term “Line of Beauty” — a line with a certain serpentine grace, not just an aesthetic preference but a foundational principle that asserts the visual and emotional superiority of the S-shaped curve. This line, empowered by dynamic movement and rhythmic flow, connects deeply with the human predilection for patterns that mimic the natural world.

Hogarth's theory, which posits a direct correlation between this serpentine line and the perception of beauty, though with no proven scientific conclusion, has been influential across art and design, suggesting that our aesthetic judgments are perhaps rooted in innate preferences for certain forms and shapes.

Beyond Hogarth's theories, Wassily Kandinsky's "Point and Line to Plane" is a profound exploration into the foundational elements of art composition, namely points, lines, and planes, and their roles in articulating the spiritual and emotional dimensions of art.

Kandinsky likens the process of painting to musical composition, where colours function like keys on a piano, eliciting emotional vibrations in the soul. This belief in the emotive power of art is reflected in his paintings such as "Composition VIII" and "Yellow-Red-Blue," where the arrangement of shapes and colours transcends visual aesthetics to invoke deep emotional and spiritual responses. These works exemplify how the interaction of geometric elements within a composition can symbolize various aspects of the human experience, from spiritual enlightenment to inner conflicts and stability, thereby creating a visual language that communicates far beyond the tangible.

In advocating for art that bridges the objective with the subjective, Kandinsky positions the artistic process as a journey toward discovering harmony and balance between universal truths and personal expression, highlighting the line's capacity to transcend its physicality and touch upon the emotional and the sublime.

ABOVE IMAGES:

Vassily Kandinsky, Composition 8, 1923, Oil on canvas, 55 1/4 x 79 inches (140.3 x 200.7 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, By gift. © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Vassily Kandinsky, Yellow, Red, Blue, 1925, Oil on canvas, 50 1.4 x 79 1/4 in. (128 x 201.5 cm). Courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Agnes Martin's "Friendship," from 1963, challenges first impressions, especially when viewed online. This painting, measuring over six feet square, incorporates gold leaf and oil, a choice of materials that adds a luminous quality to the work. "Friendship" is characterized by Martin's signature use of precise, hand-drawn lines that form a grid-like pattern across the canvas. These lines, while seemingly uniform from a distance, reveal upon closer inspection a human touch—slight variations and imperfections that imbue the piece with a subtle, vibrant energy.

Agnes Martin's life, characterized by solitude and a profound connection with her inner world, fueled her artistic vision. Despite her mental health challenges, Martin pursued tranquility and order, finding inspiration in moments of clarity for her works. Her works embody tranquility and introspection, demonstrating the line's ability to convey vast emotional landscapes within the confines of simplicity.

ABOVE IMAGES:

Agnes Martin, Friendship, 1963, Gold leaf and oil on canvas, 75 x 75 inches (190.5 x 190.5 cm). Copyright © 2024 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Detail of Friendship

The expressive versatility of the line is powerfully presented in Cy Twombly's work, where scribbles and gestural marks transcend mere abstraction to evoke historical narratives, emotional depth, and a tactile sense of immediacy. Twombly's "Untitled (Bacchus Series)" is a profound celebration of the mythical god of wine, Bacchus, characterized by dynamic lines and rich, earthy colours that evoke the essence of ecstasy and celebration. Twombly's "Bacchus" series exemplifies how abstract lines can become laden with meaning, both chaotic and restrained, transforming the act of mark-making into a narrative and expressive gesture that bridges the gap between the historical and the modern, the personal and the universal.

ABOVE IMAGES:

Cy Twombly works from the Bacchus series on display at the Tate.

Cy Twombly, Untitled (Bacchus), 2008, acrylic on canvas, 125 x 184 1/4 inches (317.5 × 468.3 cm). © Cy Twombly Foundation

“I try to organise a field of visual energy which accumulates until it reaches maximum tension.”

- Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley's works, particularly works such as "Descending" and “Fall” showcase the line's ability to create illusion and manipulate perception. Through precise arrangements, Riley's lines engage the viewer in a dynamic visual experience, challenging perceptions and highlighting the line's power not just to depict, but to activate, and actively alter the viewer's sensory experience. In “Fall” Riley repeats a single line to create optical frequencies, akin to addressing Hogarth’s “Line of Beauty” in varying degrees, challenging not only the singularity of a curved line, but also the perception of beauty created by s-curves.

ABOVE IMAGES:

Bridget Riley, Descending, 1965, Emulsion on board, 36 x 36 inches (91.5 x 91.5 cm). © Bridget Riley 2018. All rights reserved, Courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers.

Bridget Riley, Fall, 1963, Polyvinyl acetate paint on hardboard, 55 1/2 x 55 1/4 inches (141 × 140.3 cm). © Bridget Riley 2020. All rights reserved.

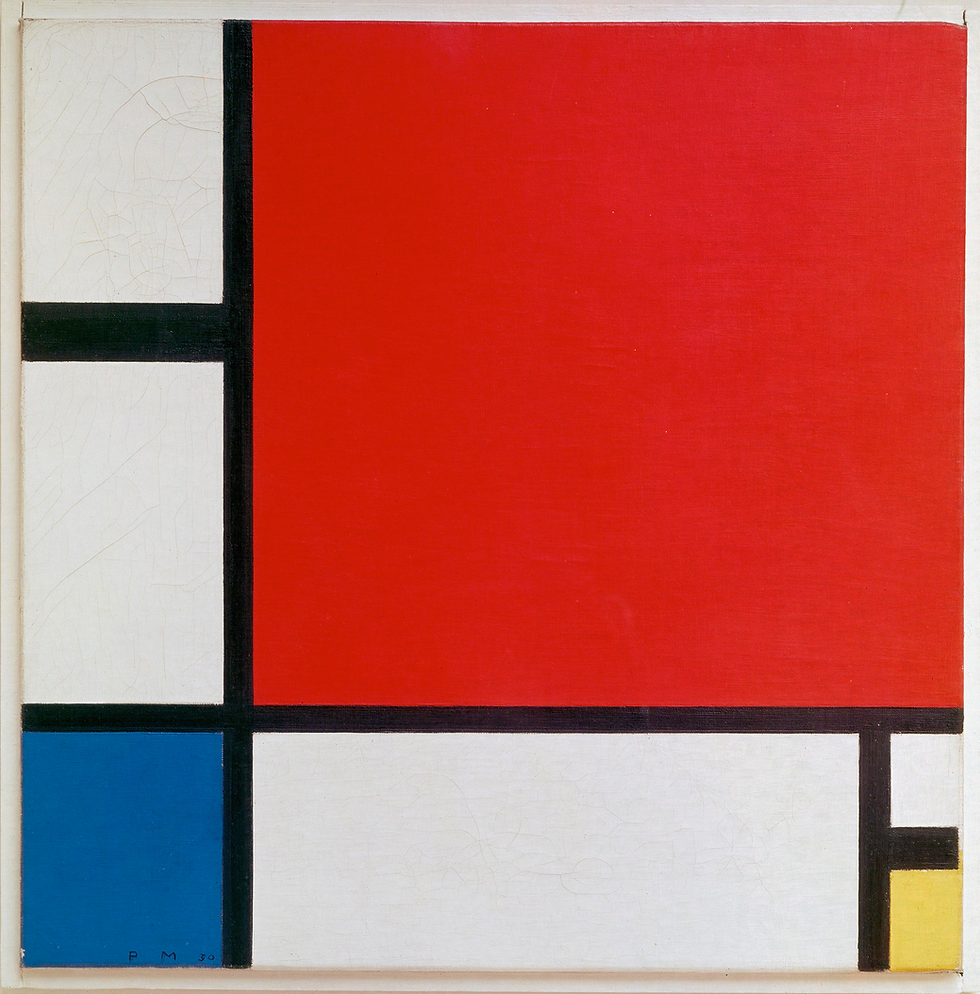

Piet Mondrian's exploration of the line reduces art to its essentials. His “Pier and Ocean” series reduces the landscape to arrangements of vertical and horizontal lines, pushing beyond Cubism’s strategy of fragmented forms and moving towards pure abstraction. His work "Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow", with a very similar line usage strategy, accented by only primary colours, articulates a vision of universal harmony and balance. Mondrian’s work distils the chaotic complexity of the world into a harmonious order, demonstrating the line's capacity to present abstract principles and convey a sense of purity and equilibrium.

ABOVE IMAGES:

Piet Mondrian, Ocean 5, 1914, charcoal and gouache on paper/homosote panel, 34 1/2 x 47 1/4 inches (87.6 x 120.3 cm). Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow, 1930, oil on canvas, 18 x 18 inches (46 x 46 cm). Kunsthaus Zürich.

The line's significance extends beyond individual artists or movements, tracing back to the earliest forms of human expression. From the cave paintings of Lascaux, where lines delineated the contours of animals and human figures, to the intricate line work of Islamic calligraphy, where lines serve both an aesthetic and a spiritual purpose. In East Asian art, the line's fluidity and expressiveness are central to the practice of ink painting, where the brushstroke's weight and speed convey a range of emotions and atmospheres.

In modern discussions, the line is a focus for both exploration and creativity. Today's artists use digital tools to push lines beyond traditional limits, as seen in Thom Mayne's spatial investigations. This extends the conversation on the line's visual, emotional, and conceptual reach. Artists like Julie Mehretu depict intricate, yet structured urban scenes through layered lines, while Fred Sandback uses minimalist lines to define space and volume, similar to Charlotte Wall, and Alexander Jowett’s transformation of vast space into linear forms on a two-dimensional surface.

ABOVE IMAGES:

Thom Mayne, XCD_20230223-054354_102-48, 2023, UV ink on aluminum, 48 x 48 inches (121.9 x 121.9 cm). Image credit: Kyle JuronDetail of Thom Mayne’s XCD_230916-113550_359-WW

Julie Mehretu, Congress, 2003, ink and acrylic on canvas, 72 x 96 inches (182.88 x 243.84 cm). © Julie Mehretu.

Julie Mehretu, Cairo, 2013, ink and acrylic on canvas, 120 x 288 inches (304.8 x 731.52 cm). © Julie Mehretu.

Fred Sandback, installation view, Dia:Beacon, Beacon, New York, 2016. © The Fred Sandback Archive. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York.

Fred Sandback, Untitled (One of Four Diagonals), 1970, black elastic cord; situational: spatial relationships established by the artist, dimensions variable. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. © Fred Sandback Archive Photo: NGC.

Charlotte Wall, Shelter (For Mark), 2022, 441 threads and shells, 120 x 120 x 120 inches (304.8 x 304.8 cm)

Alexander Jowett, Mountain Moon, 2023, acrylic and oil on canvas over wood panel, 48 x 48 inches (122. x 122 cm)

The presence of line remains a potent and versatile tool for artistic expression, and its relevance and significance requires meaningful and in depth research, exploration, and dialogue. The exploration of the line in art reveals a fundamental aspect of human creativity and perception. It is a testament to the line's enduring power and versatility, capable of conveying the complexities of the human condition, the natural world, and the realms beyond our immediate comprehension. Through its simplicity and its complexity, the line invites us to see, to feel, and to imagine, bridging the gap between the visible and the invisible, the tangible and the ineffable.