Copy of a Copy of a Copy

- Diamond Zhou

- 5 days ago

- 11 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

January 31st, 2026

By Diamond Zhou

Paul remembered a line from The Moderns as “They are a bunch of imitators imitating a bunch of imitators.” It is exactly the sort of line that should exist in that film, so for accuracy sake, we looked it up. The first thing that surfaced was not Paul’s line, and not even The Moderns, but the sentence: “Everything is a copy of a copy of a copy.” The irony is not merely that it is not from the film we had in mind, the irony is that our entry point performed the very condition we are discussing: a quotation circulating, detached from its proper source, strengthened by repetition rather than accuracy. It is also a useful reminder to anyone who writes about art for a living that attribution is not a clerical detail, attribution is a theory of value in miniature: what we believe is worth naming, what we are willing to let blur, and how quickly a phrase can acquire authority once it becomes convenient.

Copying is not a marginal activity in art. It is central to how art is made, taught, transmitted, and priced. The copy trains technique, stabilizes traditions, propagates styles, and supplies the market’s appetite for scarcity and myth. The only reason copying still reads as slightly embarrassing in North America is that we have inherited a moral frame that treats originality as virtue and imitation as failure. That frame is historically specific, pedagogically consequential, and, in many cases, intellectually lazy.

There is a phrase that demonstrates this moral perfectly: “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.” The saying is widely associated with Charles Caleb Colton, that imitation is presented as a compliment paid upward, the lesser acknowledging the greater. Oscar Wilde’s importance is that he took that polite sentence and made it socially honest by naming what the polite version conceals. His expansion, “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery that mediocrity can pay to greatness” gives the saying its continuing force. The key is not “flattery,” the key is “mediocrity.” That single word changes imitation from an ethical reassurance into an uncomfortable description of how cultural status works: admiration is rarely pure; it is often mixed with competition, ambition, opportunism, and the desire to borrow prestige without bearing its costs. That is why Wilde’s version persists, because it is true to the social conditions under which imitation actually operates.

The most revealing part is that this phrase itself has become unstable in the way it circulates: it is repeated, paraphrased, embellished, and confidently assigned to Wilde in forms that are not always easy to tie to a single source. The phrase thus becomes an example of what it describes. It gains power as it moves. It is “authentic” because it continues to describe a recognizable relationship between imitation, status, and cultural authority. This is not a sentimental point about language “losing authenticity”, it is a practical point about how authenticity is manufactured. In the art world, authenticity does not simply exist inside an object; it is upheld by documents, institutions, scholars, and consensus. Quotes, like artworks, do not float free of those structures, they are shaped by them.

So, when we speak about copying, we are speaking about more than technique. We are speaking about how value is assembled. To understand why Russia and China begin a young artist’s training with copying, and why North America often avoids it, we need to be clear about what copying does when it is taken seriously. Copying is not tracing, not trying to become Ilya Repin or Valentin Serov, it is just an act of reconstruction. A careful copy forces the student into the structure of the work: how the original organizes attention, how it regulates detail, what it simplifies and why, how it uses contrast, colour, and rhythm to create a coherent experience. Copying is not simply a way to “get better.” It is a way to learn what a painting is: an accumulation of choices, not a surface effect.

In Russian academic training, copying is commonly treated as foundational because the tradition is oriented toward disciplined draftsmanship and control of paint as a constructive medium. The student is asked to learn proportion, value, anatomy, and composition in a way that becomes bodily competence rather than verbal understanding. One can debate the costs of this system, but it is hard to deny what it produces: artists who can build an image with authority and confidence.

In China, copying is not only a teaching method but part of a longer cultural logic of transmission. The tradition of learning through copying has been integrated into painting and calligraphy not merely as skill acquisition but as a way of carrying forward methods, lineages, and standards. The point is not that the copy replaces invention, the point is that invention is expected to sit on top of a foundation that has already been earned.

However, North American art education, especially in the postwar period, absorbed two strong ideological commitments: first, the romantic commitment to originality and individual voice; second, a pedagogical commitment to creativity and personal expression as primary educational values, especially for children and young artists. Viktor Lowenfeld is a major figure in this history. Lowenfeld’s developmental model helped shift educational emphasis toward creativity and away from product-driven imitation. This shift became a real strength, it protected students from being trained into obedience. It expanded access and gave legitimacy to forms of visual thinking that do not look like academic realism.

But it also created a predictable weakness when simplified into doctrine: students were asked to be original before they were historically or technically literate enough to understand what originality might require. Many young artists produce work that feels original to them and is sincere in its impulse yet is structurally repetitive because they have not encountered the archive with sufficient depth. They are not “bad,” they are underexposed. They have not been trained to recognize the forms and ideas they are repeating, because copying, which forces close contact with precedent, has been framed as morally suspect.

This is not a call for North America to imitate Russian or Chinese academies; it is a call to admit that the disciplined intimacy with precedent that prevents naïve repetition and equips artists with range has been lost.

The Bauhaus complicates this further, and it is important precisely because it shows that modernism did not abolish discipline, but reorganized it. Bauhaus did not generally ask students to copy old master paintings, it asked them to study materials, perception, structure, and the fundamentals of form. Its preliminary courses were systematic and demanding, and the goal was not to abandon training, but to replace inherited academic habits with a new kind of visual literacy. Modernism, at its best, did not say “do whatever you feel,” instead, it said: learn the underlying grammar, then build.

This matters because it reframes the false choice that still haunts art education. The choice is not “copy or be free.” The choice is what kind of discipline produces what kind of freedom. Russian and Chinese academic copying produces one kind of fluency: control of representation, technical competence, and a strong sense of standards. Bauhaus training produces another: structural thinking, material intelligence, and a language of abstraction rooted in system and perception. North American self-expression models can produce emotional directness and conceptual play, but they often leave gaps in technique and historical awareness unless the student independently fills them.

In the late twentieth century, copying became a primary artistic strategy precisely because it could expose how authorship and value are constructed. Sherrie Levine’s rephotographs of Walker Evans are foundational here because they treat copying as an analytic tool: if the image is already reproduced, published, canonized, and circulated, what does originality mean, and who benefits from insisting on it. Levine’s work does not merely “borrow,” it forces the viewer to see authorship as a social function that organizes value.

Richard Prince pushes this into mass culture by rephotographing advertising imagery, making the point that many of the images we treat as cultural symbols are already manufactured commodities. When the “source” is an advertisement, the conventional moral drama around appropriation becomes unstable. The copy reveals that the original itself was designed for replication.

Elaine Sturtevant repeats other artists’ works with unsettling accuracy, not in order to counterfeit them, but to demonstrate how quickly an image becomes a template, and how much of what we call “originality” depends on context, timing, and institutional endorsement.

Photographing art is not neutral documentation, it can be a critique of display, ownership, and institutional framing. Louise Lawler is exemplary because her photographs of artworks in collectors’ homes and museums shift attention from the artwork’s internal content to its social placement: who owns it, how it is installed, what surrounds it, what kind of power it quietly participates in. That is copying as institutional analysis, not copying as theft.

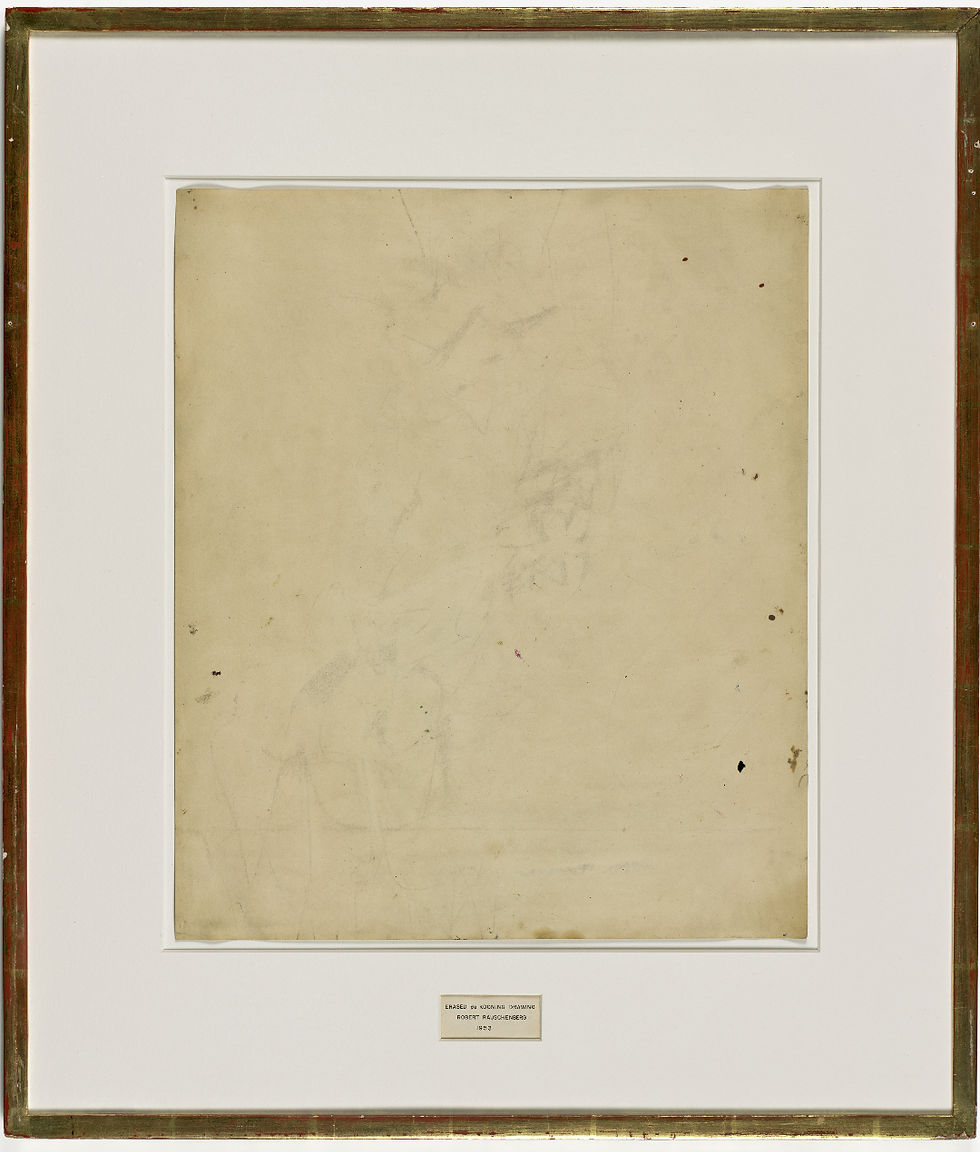

Copying can also operate through subtraction rather than reproduction. Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Willem de Kooning Drawing is not a copy in the simple sense, but it is inseparable from the logic of copying because it depends on the authority of a canonical original and turns that authority into material. Erasure becomes an authorial act, and the work becomes a question about what constitutes making.

So contemporary art did not “escape imitation,” it simply made imitation explicit, and it used imitation to interrogate the mechanisms of value. This brings us to forgery, where copying becomes both a technical act and an ethical breach. Forgery is not simply copying, forgery is copying with intent to deceive for economic gain. It exploits the market’s dependence on provenance, expertise, and narrative. The most revealing thing about major forgery scandals is not that experts can be fooled, but how easily authority can be staged when the market is hungry for a story.

Knoedler Gallery remains one of the most instructive cases in recent history because it shows the failure of due diligence within a prestige structure that should have been resistant to exactly that failure. The scandal was not only about fakes; it was about the market’s willingness to suspend skepticism when presented with the right signals.

Wolfgang Beltracchi shows a different dimension: the forger who does not merely copy a style but manufactures an alternate history, complete with plausible provenance, exploiting the fact that the market often wants the “newly discovered work” more than it wants difficult truth.

Han van Meegeren remains the classic example because his “Johannes Vermeer” forgeries reveal how connoisseurship can be softened by desire: the desire to find, to possess, to authenticate, to be the one who participates in a great narrative.

Is forgery “creation”? Technically, yes. Artistically, not in any serious sense that respects the viewer. The forger’s primary artwork is the lie, but the medium is real. That is why forgery scandals matter beyond market gossip: they demonstrate that authenticity is not an aesthetic property alone; it is a social contract maintained by institutions, documentation, and belief.

Where do imitators stop being imitators of imitators? They stop when imitation becomes metabolized rather than performed. They stop when influence is not denied but understood, selected, and transformed. This is not a romantic claim that one becomes “purely original.” It is a practical claim about artistic maturity: the artist develops enough historical awareness to recognize what they are drawing from, enough technical competence to choose rather than default, and enough conceptual integrity to disclose the terms of the relationship they are proposing to the viewer. Copying, at its best, is not submission, it is literacy.

In a culture saturated with images, the rarest thing is not novelty, it is accountability: an artist who knows what they are repeating, knows what they are refusing, and knows what they are changing.

We are living through an epoch in which copying is no longer merely a studio act, it is an infrastructure. Images reproduce at industrial scale; styles are extracted, formalized, and redeployed; archives are scraped; authorship is blurred not only by desire or opportunism but by systems that learn from what they ingest. The copy has become the default condition of visual culture, and the question is no longer whether copying happens, but what kind of ethics and literacy we build around it.

So perhaps the mature question for the art world is not, “Is this original?”, but: What obligations does this work acknowledge? What does it disclose about its sources, its permissions, its debts, its frictions? What does it ask the viewer to believe about lineage, labour, and transformation, and how does it earn that belief? In other words, can we treat attribution as more than a legal or scholarly footnote, and instead as a visible part of form, a discipline of honesty that becomes aesthetically legible?

If everything is “a copy of a copy of a copy,” the task is not to lament the loss of authenticity, but to decide what authenticity could reasonably mean under conditions of mass reproduction and artificial intelligence. Perhaps authenticity is not a mystical aura that evaporates when touched, but a practice: a set of behaviours that can be trained, demanded, and perceived. If copying is inevitable, then what forms of copying enlarge the world, and what forms merely circulate it? What does it mean, now, to copy in a way that adds responsibility, not just content? Where, exactly, do we want the next generation to learn discipline, and where do we want them to learn courage, and what happens if we finally admit that the highest practice requires both?

CURRENT

GROUP EXHIBITION

UPCOMING

The Collaborators

Nettie Wild and Friends, Films and Installations

Opening: Saturday, February 28th, 2026

1:00 - 5:30 PM

Invitation forthcoming

CONTACT US

4-258 East 1st Ave,

Vancouver, BC (Second Floor)

GALLERY HOURS

Tuesday - Saturday,

11:30 AM - 5:30 PM

or by appointment

我们提供中文服务,让我们带您走入艺术的世界。