Optical Illusion

- Diamond Zhou

- Jan 17

- 10 min read

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

January 17th, 2026

By Diamond Zhou

There is a certain kind of image that interrupts the smooth trance of looking, it triggers that small, involuntary recalibration in the body, the sensation of footing being tested, of perception catching itself mid-stride. Optical illusion in art is often treated like a clever trick, but it is closer to an existential instrument: a way of revealing how much of the world is not “out there” waiting to be captured but manufactured inside us. That is why illusion has never been a marginal indulgence, it returns throughout art history because it offers something artists have always wanted: not merely representation, but control over experience. It shares a border with the bizarre, that neighbouring terrain where logic becomes uncanny and order tips into surprise. This topic was suggested by our dear friend and devoted reader, Herb Auerbach.

Optical trickery was never only aesthetic, it was spatial politics. Consider Andrea Mantegna’s fresco cycle in the Camera degli Sposi at the Ducal Palace in Mantua. The famous painted oculus on the ceiling (completed within the broader project of 1465–1474) is not a simple demonstration of virtuosity. It is a psychological engineering feat. Stone becomes sky, the court becomes an interior cosmos, putti lean over the painted balustrade with the casual confidence of beings who belong to a realm beyond your reach. The illusion works because it manipulates a primal assumption: that the world is stable above you, that ceilings are limits. Mantegna turns the limit into a threshold, and the viewer becomes the one who is contained.

In Ferrara, the illusion becomes even more decadent, less metaphysical and more jewel-like: the Treasure Room ceiling at the Archaeological Museum of Ferrara (painted 1503–1506) is a Renaissance fantasy of ornament and depth, a demonstration of how surface can behave like carved space, how pattern can behave like architecture.

These works belong to a long European tradition of trompe-l’œil ("fool the eye") and di sotto in sù ("from below, upward") painting. What matters is the ambition: illusion as a way to alter your position in the world, where the ceiling is not a ceiling anymore, it is a claim about who gets to define reality. That same impulse appears in other guises across history: Baroque domes that dissolve into heaven, palace frescoes that create endless corridors of myth, museum rooms that expand their own authority by appearing larger than they are. Illusion has always been, in part, a form of seduction.

The modern perceptual illusion is the admission that the eye does not simply record but composes. The classic example remains the Kanizsa Triangle, first described by the Italian psychologist Gaetano Kanizsa in the mid-1950s, where a bright triangular form appears to hover forward, despite never being drawn at all. The magic is not in the image, the magic is in the viewer. Your brain performs what vision scientists call modal completion: it generates contours and brightness that are not physically present, because coherence is one of its deepest habits. The world does not arrive in neatly outlined packets; it arrives fragmented, partial, occluded, so the mind repairs it, it stitches gaps into certainty. This is not a minor curiosity; it is a profound statement about the nature of reality-as-experienced: our perception is an act of inference. We are not a passive viewer; we are a collaborator.

Surrealism pushes illusion toward something more psychological: how the mind wants to see. In Salvador Dalí’s Swans Reflecting Elephants (1937), the illusion is not an isolated trick but a worldview: a belief that reality is porous, that meaning is unstable, that the mind’s associations can overtake the visible world. Swans become elephants through reflection. The image behaves like a dream does: not illogical, but hyper-logical according to the rules of the subconscious.

Dalí didn’t treat illusion as a game of cleverness, but as a deliberate assault on the idea of fixed interpretation. His double images embody a kind of existential volatility: you are never simply looking at a thing; you are looking at your own mind deciding what the thing will be.

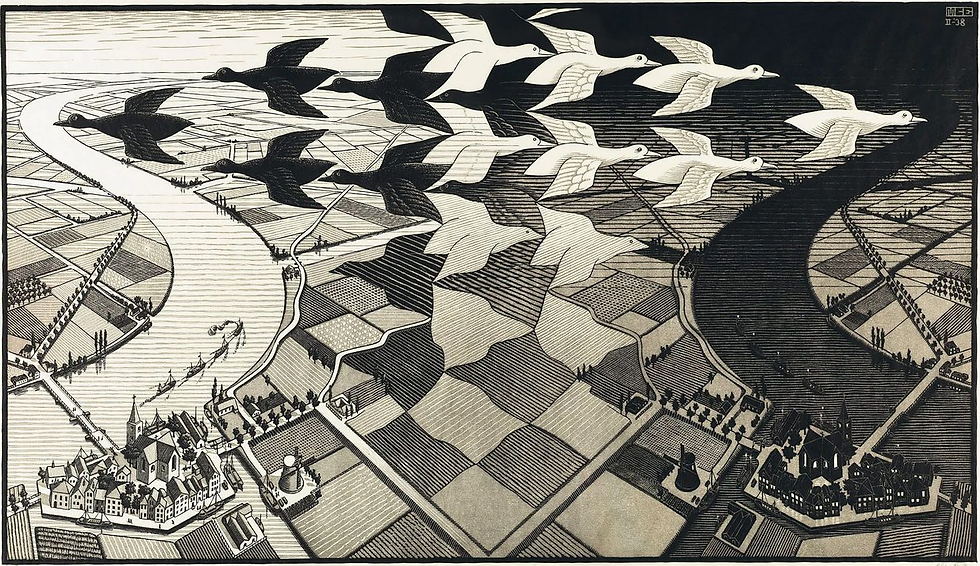

Maurits Cornelis Escher turns illusion into metaphysics. In Day and Night (1938), an orderly Dutch landscape becomes a generator of beings: birds emerge from fields as if the world itself contains an algorithm for life. Day turns into night through a seamless exchange of positive and negative space. The illusion is not merely that forms switch roles, but that the image exposes an underlying reciprocity: what you call background is simply what you have not yet recognised as figure.

And then there is Relativity (1953), that impossible architecture of staircases where gravity changes depending on who you are. People walk calmly in contradictory worlds, each obeying their own vertical logic. Escher’s genius is that he does not depict chaos, instead, he depicts coherent systems that cannot coexist. Escher’s illusions are about the terrifying elegance of structure, the way reality might be less like a window and more like a set of rules.

When The Responsive Eye opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1965, it didn’t simply popularise a look. It elevated a proposition: that modern painting could be built like a perceptual experiment, and that the viewer’s body was not incidental to meaning but the very site where meaning forms. The genius and the danger of Op Art is that it makes perception visible by making it unstable, it turns the act of looking into an event with duration, friction, and consequence.

To understand what these artists are really doing, it helps to borrow from the long argument inside perception theory. In the nineteenth century, Hermann von Helmholtz described vision as “unconscious inference,” a rapid, involuntary form of judgement that constructs the most likely world from incomplete signals. In the twentieth century, Gestalt psychology named the mind’s compulsion to complete, stabilise, and organise: closure, continuity, the hunger for whole forms rather than fragments. And phenomenology, especially Maurice Merleau-Ponty, insisted that perception is not merely optical but embodied, lived through a body that moves, anticipates, and feels its way into the world. Op Art is what happens when artists decide to paint directly into those mechanisms.

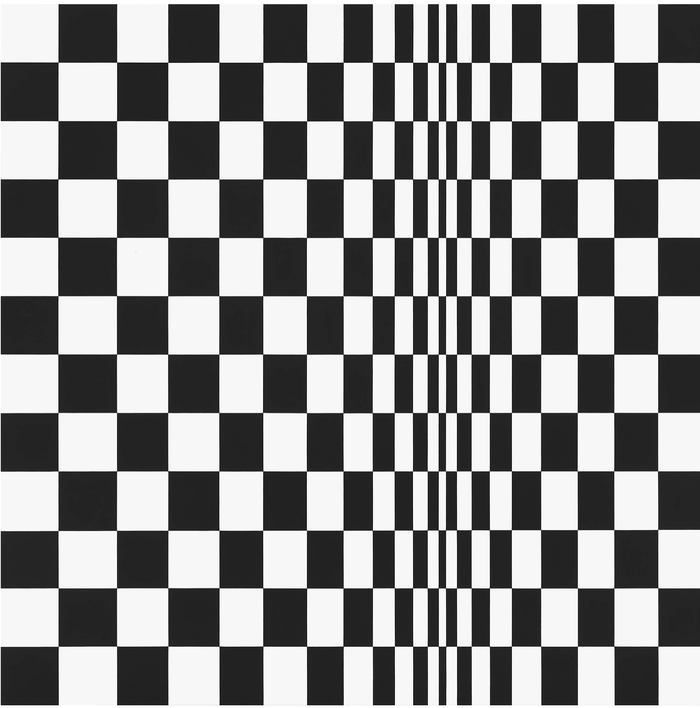

Take Bridget Riley. In Movement in Squares (1961), the image is a black-and-white grid, no symbolism, no figures, no “content” in the old sense. And yet the surface caves, flexes, tightens, seems to fold into depth as if the painting had developed musculature. Riley doesn’t paint movement, she provokes the eye into manufacturing it, exposing the viewer’s perception as a restless machine, constantly correcting itself. With Cataract 3 (1967), the instability becomes liquid, it reads like a constructed system: colour behaving like atmosphere and currents.

Victor Vasarely’s Epoff (1969) performs a modern paradox: it is flat paint on canvas, and yet it insists on becoming volume. It bulges forward as if the picture plane were a membrane being pushed from behind. What Vasarely understood, perhaps better than anyone, is that modern life was already optical long before Op Art named itself. The mid-century city is a field of engineered attention: signage, graphics, grids, rhythm, repetition. His paintings don’t merely “deceive” the eye, they mirror the era’s deeper condition, the sense that vision can be designed, managed, optimised.

This is also why Josef Albers belongs at the philosophical core of Op Art, even though his surfaces were never ostentatious. In the Homage to the Square works, nothing literally shifts, yet everything perceptually shifts. Colour advances and retreats, edges glow, harmonies turn unstable under sustained attention. Albers proves that colour is never singular, never absolute: it is relational, contingent, produced in the encounter between one thing and its neighbour. In a world that assumes seeing is objective, this is a quiet revolution, it is not only that the painting changes, it is the judgement that changes.

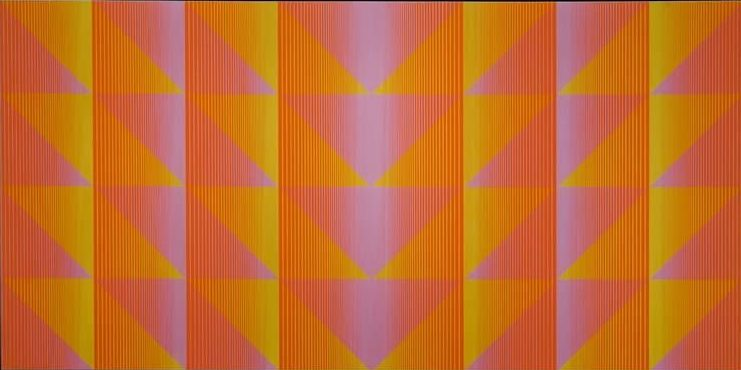

From there, Op Art fans outward into colour-mastery and optical intensity. Richard Anuszkiewicz treats hue like electricity. In Fluorescent Complement (1960), colour becomes an engine that generates afterimages and optical heat, a vibration that seems to exceed the material facts of paint. And Julian Stanczak, in works like Dual Glare (1970), pushes colour into a demand, it insists on sustained attention, and in doing so it turns sensation into a kind of discipline.

Then come the artists who make the movement’s conceptual backbone impossible to ignore. François Morellet, in Random Distribution of 40,000 Squares… (1960), uses a rule system rather than an expressive gesture, letting structure generate the perceptual encounter. The work is not only optical, it is epistemic: it asks whether the eye’s pleasure is still “natural” if the image is built by algorithmic logic. Morellet’s coolness isn’t aesthetic detachment, it’s a form of clarity. He shows that the sensation of vibrancy can be made from decisions so impersonal they nearly disappear.

In contemporary practice, optical illusion often migrates out of the canvas and into lived space, because our era is not primarily painterly, it is environmental. The image today wants to become architecture again, but with a different kind of politics: less about divine authority, more about participation. Julio Le Parc’s Continuous Instability–Light (1962) makes illusion literal, sculptural, time-based. Light and apparatus generate movement that is not “in” the work as an image but produced as a changing situation around the viewer. Here, the artwork behaves less like a picture and more like a demonstration: perception is not a fixed state, it is a living negotiation with flicker, reflection, and instability.

Jesús Rafael Soto builds optical experience out of structure, layering print and object until the eye cannot stabilise what it is seeing. His Spiral (Espiral) from Sotomagie (1955, published 1967) reads like a small portal where image becomes physical and physicality becomes perceptual uncertainty.

And then there are artists who refuse the stability of a single image altogether, turning the viewer into the missing component. Yaacov Agam’s Double Metamorphosis, II (1964) changes as you move, making perception explicitly positional. This is illusion as ethics: it says, quietly but unmistakably, that there is no single, sovereign viewpoint.

Artists like Aakash Nihalani use tape, neon geometry, and urban surfaces to create impossible apertures: shapes that appear to fold space, carve portals, or conjure dimensions that aren’t there. The illusion is quick, playful, almost comic, but it also carries a modern truth: the contemporary city already feels like layered realities competing for dominance, makes that condition visible.

In popular media, the “black hole” optical illusion circulated widely online, viewers report seeing a static centre expand, as if they are being pulled into a tunnel. Researchers describe it as the brain “predicting the future,” preparing for entry into darkness. That claim isn’t just poetic, in a peer-reviewed study published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, researchers found that these illusory expanding “holes” can produce measurable physiological effects: viewers’ pupils dilate, correlating with the perceived strength of the illusion.

This is the moment optical illusion stops being a metaphor and becomes a revelation. The image does not merely persuade your mind. It recruits your body; it triggers anticipatory mechanisms as if the world has already changed. Which means the old question, “Is it real or not?” becomes naïve. The more precise question is: if perception drives physiology, what do we mean by real? Illusion is not the opposite of reality. It is part of how reality is lived.

Optical illusion is often misunderstood as a clever failure: the viewer gets “tricked.” But the deeper story is that illusion reveals the extraordinary competence of perception. The brain is not a camera. It is a prediction engine, a pattern-maker, an editor working at impossible speed, constantly filling gaps, correcting noise, stabilising chaos. It invents edges, assigns depth, and decides what matters. Artists who work with illusion are not merely playing games with vision, they are showing you the seams of consciousness.

In our current era, where screens train us to accept synthetic realities without question, illusion in art feels newly urgent. Because it teaches us a rare kind of literacy: the ability to detect when perception is being guided, when attention is being manipulated, when the world you are experiencing is not simply “what is there,” but what you have been trained to assemble.

Illusion makes a quiet demand: look longer, look harder, admit how much of seeing is believing, and how much of believing is simply the brain trying to survive uncertainty with elegance. And perhaps that is optical illusion’s final gift: a reminder that reality is not something we possess, it is something we participate in, continually, imperfectly, beautifully.

CURRENT

GROUP EXHIBITION

UPCOMING

The Collaborators

Nettie Wild and Friends, Films and Installations

Opening: Saturday, February 28th, 2026

1:00 - 5:30 PM

Invitation forthcoming

CONTACT US

4-258 East 1st Ave,

Vancouver, BC (Second Floor)

GALLERY HOURS

Tuesday - Saturday,

11:30 AM - 5:30 PM

or by appointment

我们提供中文服务,让我们带您走入艺术的世界。