Writing Honestly About Art

- Diamond Zhou

- Sep 20, 2025

- 12 min read

Updated: Oct 11, 2025

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

September 20th, 2025

Visual art does not begin in paragraphs. It begins with decisions about scale, medium, composition, or colour, made in silence. Only afterward do the words arrive, and they arrive in abundance: in catalogues, reviews, statements, manifestos, lectures. Around each work, language forms a frame, sometimes clear, sometimes ornate, sometimes so heavy that the work itself nearly disappears behind it. The question is not whether art needs words, but what kinds of words art deserves.

This is not a new question. Giorgio Vasari, the sixteenth-century painter, architect, and writer, gave Renaissance art its prose in his Lives of the Artists. His anecdotes, some accurate, others more legend than fact, made Giotto, Leonardo, and Michelangelo into enduring figures. Without Vasari’s biographies, much of that history would have remained scattered across archives. From the start, writing has been not only accompaniment but preservation, how art survives beyond its moment but into history. Silence may be the naissance of art, but language has long been its inevitable companion.

When I think about art writing that justifies itself, I begin with the voices I know best. Roald Nasgaard has written with patience and formality about Canadian abstraction. His sentences are deliberate; each painting placed in careful relation to others. In Abstract Painting in Canada, he resists both parochialism and dependence, showing how Canadian abstraction developed across distinct regions and decades: Automatistes, Painters Eleven, Plasticiens, Emma Lake, forming a self-sustaining history rather than a mere echo of foreign trends.

Karen Wilkin writes with another kind of clarity. Her criticism, whether on Stuart Davis, David Smith, or Helen Frankenthaler, is guided by the eye. She insists on the discipline of description, what is actually there, before metaphor takes over. Her sentences do not seek to overwhelm but to steady. Reading her, one feels the simple dignity of criticism as a practice of looking hard and reporting honestly.

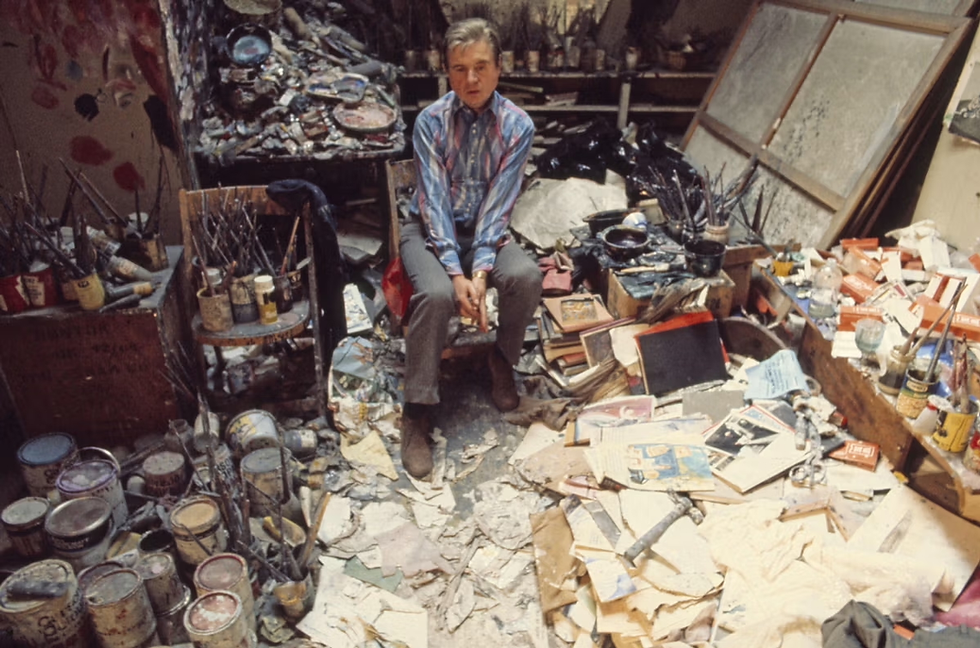

The Francis Bacon interviews are a touchstone because they show what art writing can do when it refuses to pretend. David Sylvester accepts that language will fall short, and he keeps working anyway. He listens, asks again, allows contradictions to remain, and leaves space where certainty would be false. The result is not closure but clarity about the difficulty. For Bacon the aim is simple and extreme, images taken directly from the nervous system, the impact a visual shock. Sylvester will not spin that into theory. He leaves the claims where they belong, near the paint and the chaos, and trusts the reader to test them. What he offers is not closure but a practical honesty about how meaning forms.

Robert Hughes and Peter Schjeldahl remain for me the most instructive voices on the dangers of art-speak. Hughes thundered against it, warning that “newness as such, in art, is never a value.” He believed that writing about art was part of its civic life and therefore owed clarity to its readers. Schjeldahl made the same point in a lighter register. “With art criticism it’s difficult to discuss beauty… because there’s always the possibility that we’re insane,” he joked. His reviews sparkled with wit, but the wit was always intentional, it was there to keep the reader awake, alert to the fact that art is a living encounter, not a professional ritual. Between Hughes’s thunder and Schjeldahl’s conversational ease, one sees two models of criticism that resist “Art speak” without abandoning seriousness. Rosalind Krauss, by contrast, shows what happens when theory is applied with discipline and necessity. Her writing is dense, but not gratuitous.

If critics have found ways to speak, artists often falter. For so many artists, artist statement has become a dreaded task. The difficulty is partly practical. Much of what an artist knows is tacit, embedded in the eye, the hand, the rhythm of trial and error. To compress that embodied knowledge into sentences feels like a loss, a betrayal of the medium’s silent intelligence.

The problem is also emotional. An artist is too close to their own work, too entangled in its birth, to achieve the detachment that writing requires. Barnett Newman tried, with manifestos such as The Sublime is Now, declaring that “the impulse of modern art is the desire to destroy beauty,” but his prose often became more metaphysical than clarifying. Donald Judd’s writings, by contrast, were pared down to aphorisms: “A work only needs to be interesting,” he remarked, a sentence as spare and resistant as his sculpture. The Dadaists and Surrealists turned language into a weapon of performance, manifestos as events rather than explanations. But these examples are exceptions. Most artist writing either slips toward self-mythology, casting the artist as the hero of their own story, or toward opacity, mistaking vagueness for profundity.

Sarah Thornton’s book 33 Artists in 3 Acts makes this dynamic visible. Her book is not criticism but anthropology, tracking how artists present themselves in studios, interviews, and public appearances. Divided into acts of politics, kinship, and craft, it shows that language is not only commentary but performance. Thornton observes that artists often speak strategically, using words to construct reputations as much as to describe work. One passage describes Marina Abramović’s careful self-staging, while another shows Ai Weiwei leveraging blunt statements into global attention. Thornton’s point is subtle but crucial: the struggle over words in art is not only about critics and curators. It is about how artists themselves fashion their identities. Words circulate as currency in the art world, accruing value, shaping careers.

This explains why the artist’s statement often feels alien. It is a performance of self just as much as it is an explanation of work. Thornton reminds us that language, even when uncomfortable, is unavoidable. If art resists words, the art world does not.

There is something deeply unsettling about how the art world can manufacture art out of almost nothing and then invest it with significance largely through art writing. We like to call this phenomenon the “psychosis of art” because it reflects a looping system: artworks too insubstantial to stand on their own get propped up by critics, institutions, and jargon; in turn, that applause gives legitimacy to more such works. It is not just art-speak that is the problem, it is the artworks, the system, and the mutual reinforcement.

Robert Hughes put it with characteristic bite: “The obscurity and pointlessness of most conceptual art was made worse by the language in which it came wrapped.” He cited Art-Language, the journal of the movement, where one essay began, “Supposing that one of the quasi-syntactic individuals is a member of the appropriate ontologically provisional set—in a historical way, not just an a priori way (i.e., is historical); then a concatenation of the nominal individual and the ontological set in Theories of Ethics (according to the ‘definition’)…” Hughes hardly needed to comment on the passage, the language condemned itself. What should have been laughed out of court instead passed for rigour, protected from scrutiny by its opacity.

Even Lucy Lippard, one of conceptual art’s most ardent defenders, admitted the irony: “Hopes that the conceptual art would be able to avoid the general commercialization, the destructively ‘progressive’ approach of modernism were for the most part unfounded.” Whatever minor revolutions in communication had been achieved by dematerialising the art object, Hughes concluded, “art and artist in a capitalist society remain luxuries.” In other words, stripping art down to paper, diagrams, or absence of any physical presence didn’t break the system. It simply made it easier to recycle stale or trivial ideas in the name of “criticality,” keeping the market turning.

This was her warning, and it remains ours. When writing curdles, it props up faint ideas and trains the audience to mistake obscurity for depth. What should wither in daylight instead lingers on, encouraged by critics who confuse difficulty with seriousness.

An interior earth sculpture. 250 cubic yards of earth (197 cubic meters)

3,600 square feet of floor space (335 square meters). 22 inch depth of material (56 centimeters). Total weight of sculpture: 280,000 lbs. (127,300 kilos)

The New York Earth Room (1977) is the third Earth Room sculpture executed by the artist, the first being in Munich in 1968. The second was installed at the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, West Germany, in 1974. The first two works no longer exist.

The New York Earth Room has been on long-term view to the public since 1977. This work was commissioned and is maintained by Dia Art Foundation.

A banana taped to a wall by Maurizio Cattelan or an empty bottle on the ground can be clever or provocative, but too often they are elevated far beyond their merit by a chorus of critics eager to declare them brilliant. Hughes warned against this inflationary cycle: “Some new works of art have values of some kind or another. Others, the majority, have little or none. But newness as such, in art, is never a value.” Innovation without depth is not progress. Yet novelty is what institutions and markets crave, and critics supply the words that give novelty its price.

The result is alienation. To much of the public, the art world appears deranged, celebrating trivial gestures while neglecting the works that require concentration, skill, and knowledge. Art is not everything, yet critics often write as if it were. The psychosis of art is precisely this: a system that rewards the flimsiest ideas because they can be dressed in theoretical grandeur, while more difficult and disciplined practices are overshadowed.

I felt this acutely as a student, sometimes working through readings so esoteric and obscure that a long sentence had to be dismantled piece by piece to be understood (Sometimes I wondered if it all had to do with the fact that English is my second language). Words were invented for specific theoretical contexts and were useless elsewhere. Perhaps, I often wondered, language is insufficient, perhaps words must be invented to capture new realities. But more often I felt the opposite, words were being invented for the sake of performance, not precision. Good writing does not flaunt its difficulty, instead it reaches across it. The best art writing gets profound and significant ideas across, not by disregarding the reader but by respecting them.

This tension is visible in Canadian art as well. The Painters Eleven, in Toronto in the 1950s, refused manifestos, insisting there were no rules, no jury, no statement. Yet the refusal of words was itself a declaration, and soon enough critics supplied the necessary framing. At Emma Lake in Saskatchewan, where artists gathered with visiting critics like Clement Greenberg, the clash of perspectives was instructive. For some, the infusion of theory gave new ambition. For others, it felt like imposition, words from New York weighing too heavily on prairie studios. Jack Shadbolt wrote copiously about art, his Act of Art an extended meditation on creativity and culture. At times insightful, at times self-mythologizing, it demonstrates the double-edged nature of artist writing. Roald Nasgaard’s histories have provided a counterbalance, grounding abstraction in Canada with rigour and patience, securing it against both neglect and overstatement.

Writing about art begins in love. It is steady interest that turns into service, a story told on someone’s behalf. It is speaking for the artists and telling their story to a listener who cannot see, perhaps to someone who has never seen at all. How do you tell a blind reader the beauty of a sunrise, the colour of the sky at dusk. You try with a whole story, honest and complete, bright where it must be and quiet where it should be, carrying a little mystery and a touch of humour. Good art writing is not a list of facts or a parade of theory. It makes the unfamiliar familiar. It takes a reader by the hand and sets that hand on the surface of the work, lets them feel the cool lick of paint, the slight rise and fall of a line, the moment before a colour occupies a void, until the heart begins to answer back. Writing should stir people. It should draw tears, kindle desire, spark anger, send a room to its feet or bring a single person to stillness.

The task is harder than it sounds. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then art writing must be worth more than that, it must be sufficient to hold the excess, to translate something already beyond language. When words seize up, when they are congested with jargon or hollow invention, they betray the work. They fail the artist, and sometimes they fail a whole generation. History is built not only by those who live it, but by those who write it. The fate of artists is too often decided in words. Because writing is how art is remembered, it carries responsibility. Too many lives were left in the margins when writers looked past them, women and disenfranchised artist were denied attention. Renewed care has brought many back, not by inventing merit but by finally naming what was there. In this way art writing does more than describe. It builds a common ground. It keeps faith with the work and with the people who will come looking for it.

Writing is a discipline of thought. It slows the rush of impressions, forces choices, exposes weaknesses. There is joy in this process, the moment when a phrase finally captures what one has seen, when an argument crystallises. But there is also danger. Words intoxicate. It is easy to fall in love with one’s own eloquence, to mistake flourish for insight. This is the narcotic engine of art-speak, where sentences that feel profound to write but collapse under reading. The discipline of criticism is to resist that intoxication, to write not only beautifully but truthfully.

What, then, makes a good art writer? It is not someone who invents words to impress, or who launders weak art into brilliance through jargon. It is someone who clarifies without flattening, who judges without cruelty, who respects both the work and the reader. Good art writing does not obscure; it illuminates, and it does not alienate; it invites. So, does art need words? It needs some. Without them, much would vanish into obscurity, context, history, memory, debate. But art does not need inflated words, words that drown out perception. The kinds of words that help are modest, they ought to describe before they interpret, they acknowledge limits, they serve the reader. Art writing is best thought of as a bridge. It spans the gap between the artist’s silence and the viewer’s experience, between the present and the historical record. A bridge is not the destination, but without it the crossing may never happen.

Join us on Saturday, September 27, for a musical interlude with our resident violinist John Marcus. Live performances in three sessions (15 minutes each) beginning at 3:00, 4:00, and 5:00 PM at the gallery. Visit the exhibition and linger for exceptional live music.

Please stay tuned for more information.

Warm congratulations to Sarah Macaulay on opening her new home for Macaulay + Co. Fine Art and CEREMONIAL / ART at 3712 W 10th Ave, in the Khatsahlano/Kitsilano neighbourhood. We will miss her presence in The Flats, but we are delighted to see this next chapter take shape.

CURRENT

GROUP EXHIBITION

This exhibition gathers artists whose practices transform material and perception into experiences that linger, works that shift the way we see light, inhabit space, and feel the weight and presence of form. United by a balance of beauty and thought, these pieces invite us to step into moments where looking becomes a deeper act of seeing. Exhibition features works by Michael Bjornson, Edward Burtynsky, James W. Chiang, Ronald T. Crawford, Gathie Falk, Deirdre Hofer, Jan Hoy, Robert Kelly, Joseph Kyle, Marion Landry, James O’Mara, David Spriggs, Charlotte Wall, and many more.

CONTACT US

4-258 East 1st Ave,

Vancouver, BC (Second Floor)

GALLERY HOURS

Tuesday - Saturday,

11:30 AM - 5:30 PM

or by appointment

我们提供中文服务,让我们带您走入艺术的世界。