Picasso Ceramics

- Diamond Zhou

- Sep 12, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 11, 2025

welcome to our

SATURDAY EVENING POST

September 13th, 2025

Pablo Picasso’s ceramics were often introduced as a late diversion, the master playing with pots in the sun after the intense storm of Cubism and Guernica. That cliché collapses the rigour, the ambition, and the sly conceptual wager of the undertaking. Picasso first visited Vallauris in 1946 and met Suzanne and Georges Ramié, owners of the Madoura pottery; by the autumn of 1947 he was back, working daily in their workshop and soon settling nearby with Françoise Gilot and their children. Picasso made clay into a laboratory where sculpture, painting, printmaking, and design converged. Anything but marginal, the ceramic project became a post-war pivot where Mediterranean antiquity meets modern reproducibility, and the commonplace table doubles as an avant-garde arena.

Picasso’s turn to clay is inseparable from the place. Vallauris had been a ceramics town since the Gallo-Roman era, and its fireclay supported centuries of domestic wares and, in the nineteenth century, Massier-era artistic innovation. In the 1950s, with Picasso resident nearby, it became again a locus of revival. The municipality’s own histories are explicit: “2000 years of pottery,” a craft infrastructure that predates modern art yet proved ideal for it. Picasso, in turn, assumed a civic role. He gifted the bronze L’Homme au Mouton to the town (modeled in the war years, installed publicly in 1949–50) and painted the monumental La Guerre et la Paix for the chapel of the old priory (installed 1954; a third panel added 1958), a definitive anti-war statement that now forms the core of the National Picasso Museum in Vallauris. These acts braided his ceramic practice to a broader, public-facing project of Mediterranean humanism.

Clément Massier’s turn to metallic lustre glazes was prompted by Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, who joined him as a collaborator in 1887. A collector of Hispano-Moresque ware, Spanish earthenware finished with iridescent copper, gold, and silver glazes. Lévy-Dhurmer left a clear mark: the bright, reflective surfaces define the works he produced during his nine years in Massier’s studio. Massier, in turn, kept pursuing lustre effects well after Lévy-Dhurmer’s departure in 1896.

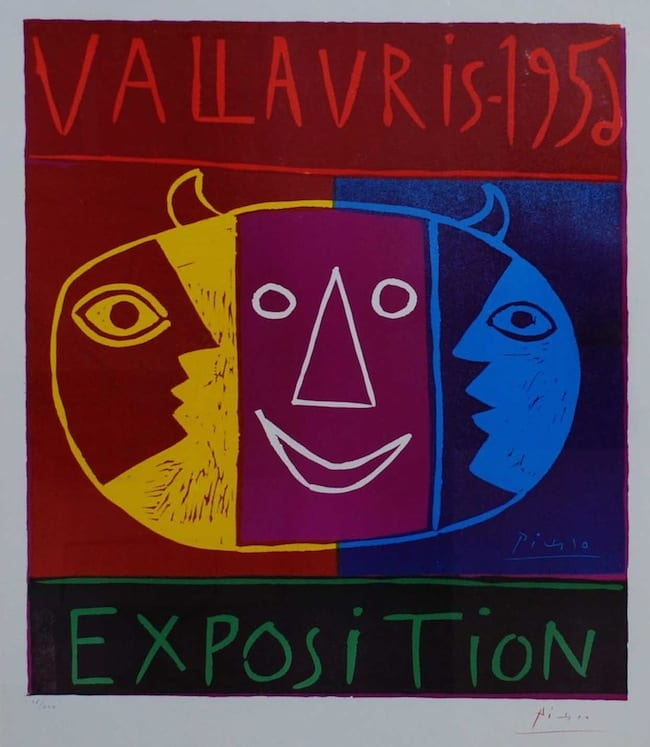

Just as crucial was Vallauris as printing ground. Working with the local printer Hidalgo Arnéra, Picasso developed a suite of linocut posters, the festival and pottery-fair announcements from 1951 through the 1960s, whose broad gouged planes rhyme with his carved and pressed clays. The Metropolitan Museum’s Ceramics Exhibition, Vallauris, Easter 1958 and Vallauris Exhibition 1958 sheets are emblematic: relief thinking translated into public graphics.

Inside Madoura, Picasso’s ceramic practice unfolded along two entwined tracks: singular invention and serial dissemination. Between 1947 and 1971 Picasso designed 633 distinct ceramic editions, alongside unique works and variants. The workshop standardized a family of marks: “Madoura Plein Feu,” “Edition Picasso,” “Empreinte originale de Picasso,” and in later work “Poinçon original de Picasso” that codified place, process, and collaborative authorship. “Date of conception,” a standard entry in sale catalogues and museum records, often precedes later execution, typical of editioned ceramics realized over years under Picasso’s supervision.

In the “Empreinte” (imprint/trace) method, Picasso incised or modelled a design in a dry clay (or plaster) matrix; pressed into fresh clay, it yielded a reversed impression that could then be decorated and glazed, which is printmaking logic enacted in earthenware. Late in this body of work, Poinçon stamps, which are tiny punch marks engraved in linoleum and impressed into clay extend that relief analogy to the level of the mark itself. In short: the plate becomes a print matrix; the pot, a rotary sculpture with a skin that reads like a relief.

Edition sizes varied by ambition and model, typically from 25 to 500. Contemporary guides and auction scholarship have long emphasized that this was not a diminishment of art but its redistribution: multiples meant to be lived with rather than sequestered. If this serial logic links clay to print, the material intelligence of the objects, such as how they are made, not merely multiplied, anchors the work to sculpture and painting. Picasso draws with engobe (slip) across white earthenware, incises into leather-hard bodies, and exploits sgraffito to toggle line and ground. On certain plates he uses oxidized-paraffin halos at the rim and even abrades raised outlines to sharpen relief, which becomes tactility edited by abrasion.

Picasso worked across an encyclopaedic array of forms: round and oblong dishes; round-square plates; pitchers that become owls, fauns, or women; convex wall plaques; tiles; amphorae whose silhouettes cue Greece, Etruria, and Iberia. Each form is purposeful, handles become horns or ears; a spout is promoted to a nose; the belly of a pitcher doubles as torso or moon. The motif of owl is almost biographical. In 1946 at Antibes, the sculptor-photographer Michel Sima brought Picasso a wounded owl, christened Ubu, it lived in the artist’s kitchen and entered his imagery with stubborn insistence.

Numbers and marks are not mere trade details, they are the record of a distributed authorship that is neither abdicated nor solitary. Madoura’s artisans threw, impressed, and decorated; Picasso selected models, cut matrices, intervened on fresh clay, and supervised outcomes. Stamps and cataloguing protocols guaranteed the system. (Alain Ramié’s 1988 Catalogue of the Edited Ceramic Works remains the indispensable reference, and the A.R. numbering is standard in museums and the market.)

In Chouette the turned vase becomes a bird by a sequence of inevitabilities: lip to crown, handleless shoulder to chest, a short cylindrical spout to beak. Over a dark engobe Picasso works wet-in-wet, then scores through with a boring-rod so the white earthenware flashes forward like plumage; partial glazing fixes the brush’s speed without sealing the surface into gloss. The object is not decorated so much as edited, it is drawing by subtraction, volume by abbreviation. Conceived in 1969 and issued as an edition of 500, Chouette bears the workshop’s authorship protocol “Edition Picasso” and “Madoura” stamps, codifying both the artist’s design and the atelier’s high-firing craft. The format’s scale (c. 28–30 cm high) suits domestic placement but reads powerfully across a room; it is an effigy vessel with civic poise. For the collectors, this work offers a late, lucid statement of Picasso’s “metamorphic functionalism”: an animal imagined from the grammar of a pot, not applied to it.

Photography by Kyle Juron © Paul Kyle Gallery.

On the eight-inch plate of Toros two bulls divide the field into upper and lower registers, a comic-heroic diptych the size of a breakfast dish. The coloured engobes, violet for ground, sea-green for sky, are laid broad and fast, the animals brushed in near-calligraphic black; a single tree, comically upright, anchors the horizon. The image reads like a relief print pulled in glaze: silhouettes, reserves, and haloes formed by oxidized edges are all part of the syntax. Conceived on 29 July 1952 and executed in an edition of 500, the plate carries the standard underside incised “Edition Picasso” and stamped “Madoura”.

Here the pitcher, one of Picasso’s most sculpturally intelligent forms becomes a procession. The handle rises like an arcade over the vessel’s shoulder; across the belly a rider and horse advance in a frieze of knife-engraved lines and pooled blue-black engobe. Conceived in 1952 and issued in a numbered edition of 300 (c. 21–22 cm high), the model is stamped and additionally incised “Edition Picasso” and “Madoura”, the pitcher’s white earthenware taking colour with unusual freshness. The Iberian theme is not a citation but a structure, the vessel’s curvature dictates the horse’s stride, and the rider’s profile reads at three-quarters as the jug turns. Few works declare so plainly Picasso’s belief that sculpture, painting, and design should be neighbours rather than rivals.

Photography by Kyle Juron ©Paul Kyle Gallery.

If Cavalier et Cheval is procession, Visage is apparition. This tall, slender pitcher (c. 30 cm) presents a face that is not applied to the pot so much as unfolded from it. Red-brown and black engobes sit on the white earthenware like fresco. Conceived in 1955 and issued in an edition of 500, Visage is among the clearest demonstrations of Picasso’s “effigy vessel” thinking and of Madoura’s edition discipline; underside marks “Edition Picasso” and “Madoura”

Photography by Kyle Juron © Paul Kyle Gallery.

If the 1950s market sometimes treated these ceramics as charming sidelines, scholarship and exhibition history have steadily repositioned them. The landmark “Picasso: Painter and Sculptor in Clay” (Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1998; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1999) assembled more than 170 largely unique works and mapped their dialogue with the painter’s and sculptor’s vocabularies. That project, and the substantial catalogue edited by Marilyn McCully, helped stabilise critical language for the oeuvre and embed ceramics within Picasso’s late style.

Major museums now teach from and exhibit the ceramic body of works. The Picasso Museum in Antibes holds the first large gift of Madoura pieces (78 ceramics donated in 1948); the British Museum and the NGV maintain exemplary entries that attend to technique and stamping; The Met folds the linocut posters into its story of Picasso’s Vallauris years, making visible the productive traffic between print and clay.

If one wanted a single theoretical thread, it would be this: Picasso uses clay to test how aura survives seriality. In the Empreinte series the pressure of a matrix records a touch that is original and repeatable, in unique or variant pieces the same graphic intelligence is routed through incisions and glazes that can only happen once. Either way, the result is a paradoxical intimacy at scale, a democratised preciousness. Even firing cracks and glaze crazing, where the sorts of conditions that auction specialists counsel not to treat as defects can become part of the ontology, of evidence that fire, not just the artist’s hand, is a co-author. So in the case of Picasso ceramics, for collectors and curators alike, those ceramic conditions read as history, not damage.

What these ceramics ask of us now is simple and hard: retire the boundary between “art” and “craft”; admit that seriality can carry poignancy, and recognise that ceramics can be both picture and performed making. They prefigure our porous present: design objects, limited editions, sculpture, while reminding us that reproducibility does not cancel invention.

CURRENT

GROUP EXHIBITION

This exhibition gathers artists whose practices transform material and perception into experiences that linger, works that shift the way we see light, inhabit space, and feel the weight and presence of form. United by a balance of beauty and thought, these pieces invite us to step into moments where looking becomes a deeper act of seeing. Exhibition features works by Michael Bjornson, Edward Burtynsky, James W. Chiang, Ronald T. Crawford, Gathie Falk, Deirdre Hofer, Jan Hoy, Robert Kelly, Joseph Kyle, Marion Landry, James O’Mara, David Spriggs, Charlotte Wall, and many more.

CONTACT US

4-258 East 1st Ave,

Vancouver, BC (Second Floor)

GALLERY HOURS

Tuesday - Saturday,

11:30 AM - 5:30 PM

or by appointment

我们提供中文服务,让我们带您走入艺术的世界。